The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic—including the impacts of the disease itself and of policy responses taken to reduce disease transmission—on the well-being of poor households around the world have been wide-ranging. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the global economy has contracted by around 4.4 percent since the onset of COVID-19 and that the total price tag of the epidemic will eventually amount to 11 trillion dollars (International Monetary Fund 2020). The World Bank predicts that the people most affected by the COVID-19 economic crisis are likely to be engaged in the informal service sector and living in congested urban areas marked by social distancing and mobility restrictions (World Bank 2020).

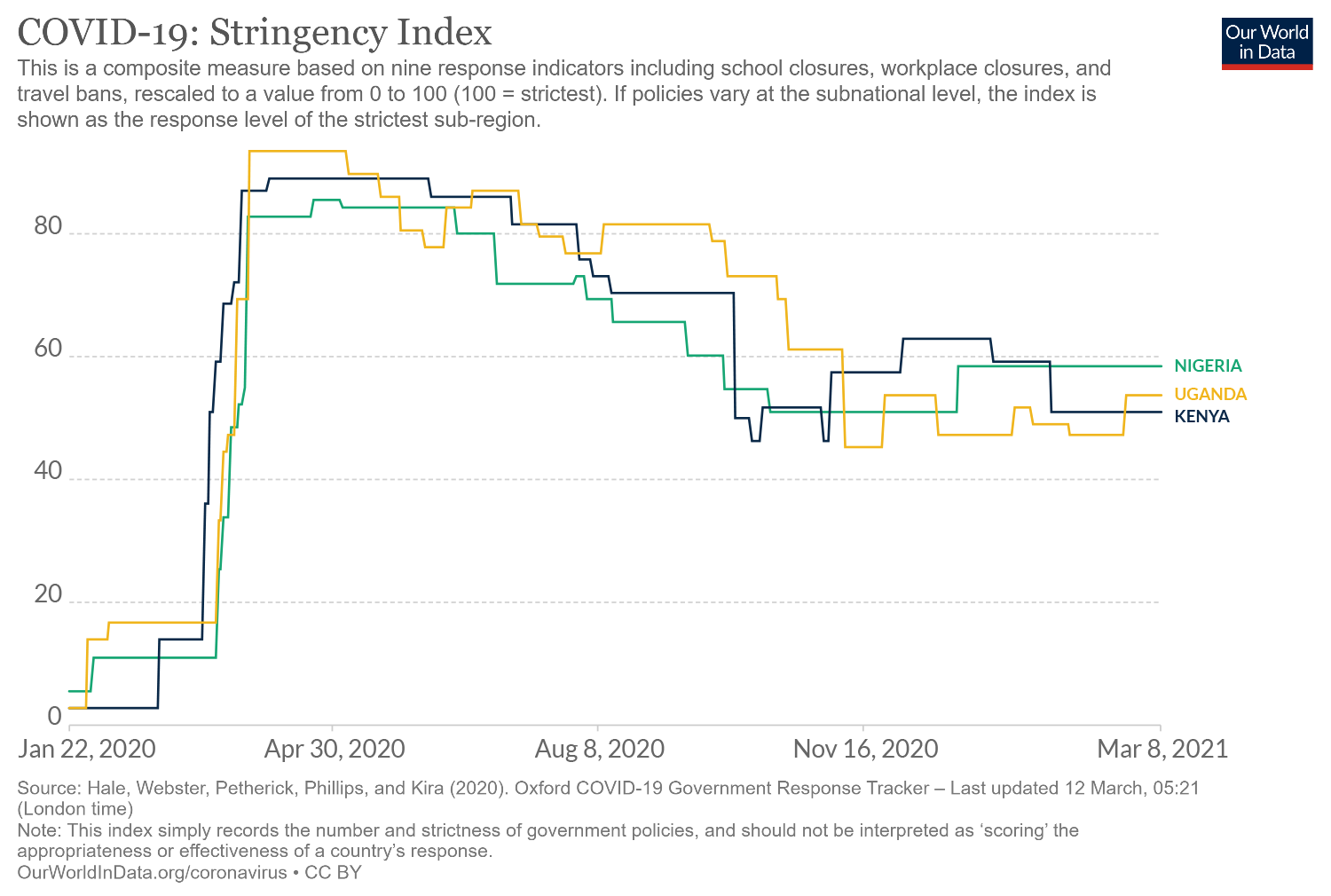

While most African countries report fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths than other continents, governments have imposed strict control measures, including closing schools and workplaces, cancelling public events and public transport, limiting gatherings, and restricting travel. The Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (OxCGRT) systematically collects information on a number of common policy responses over time and found that restrictions were introduced rapidly in Africa, as in much of the rest of the world, in mid-March 2020, and have eased slowly over the course of the past year (Figure 1). These restrictions can reduce households’ ability to work and affect their access to needed services, particularly in contexts where much of the economic activity is informal.

Stringency of government response over time in Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda

To understand how COVID-19, government restrictions, and global economic disruptions from the pandemic have affected household wellbeing, FinMark Trust worked with GeoPoll to field high-frequency cross-sectional surveys in several sub-Saharan African countries. Using an innovative approach to weight the telephone-based surveys, Mathematica was able to create nationally representative estimates to understand the impacts of COVID-19 on households. Here we focus on three African countries—Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda—to understand how COVID-19 has affected households economically, what supports have been available to households, and how households are coping with economic shocks.

Evidence of economic shocks

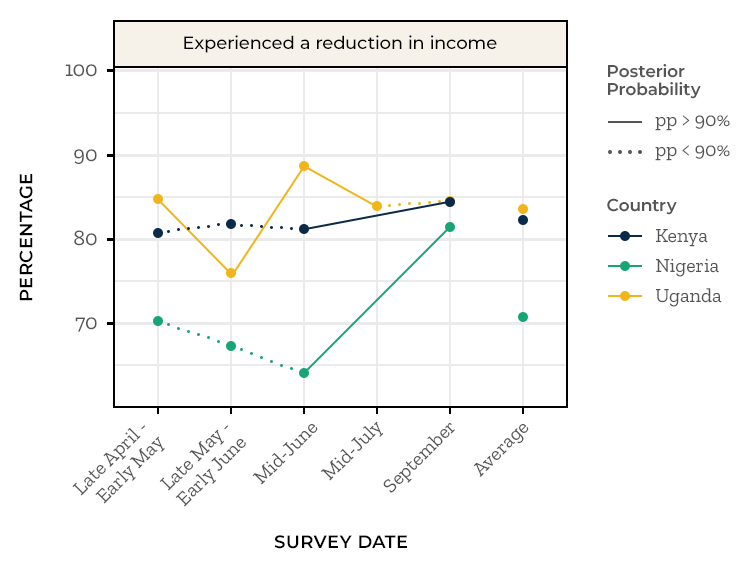

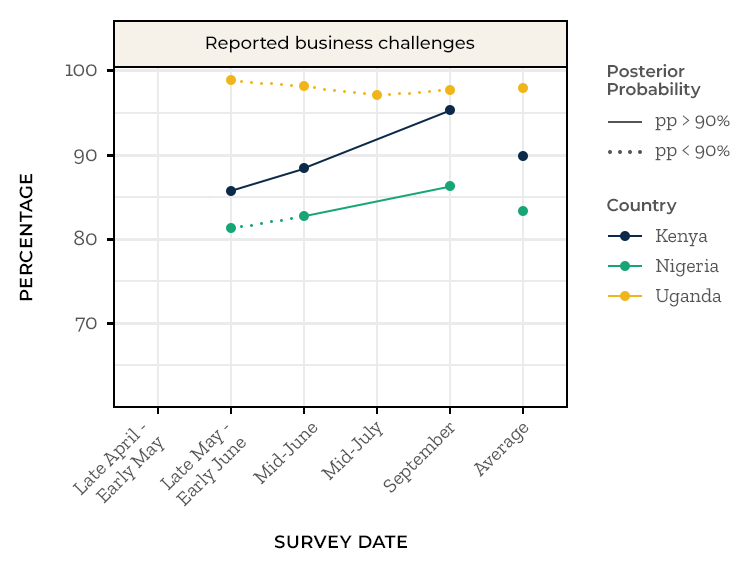

Households have experienced substantial financial insecurity since the pandemic began; a large majority report reduced income compared to the same time one year earlier and most households who have businesses report challenges with those businesses. Some measures of financial insecurity have increased over time, despite restrictions easing, suggesting that whatever coping mechanisms households had for managing economic shocks in the early months of the pandemic were insufficient to last through the many months of restrictions and economic hardship as the pandemic wore on. Rural areas were harder hit financially than urban areas, with rural households being more likely to report reduced income in all countries.

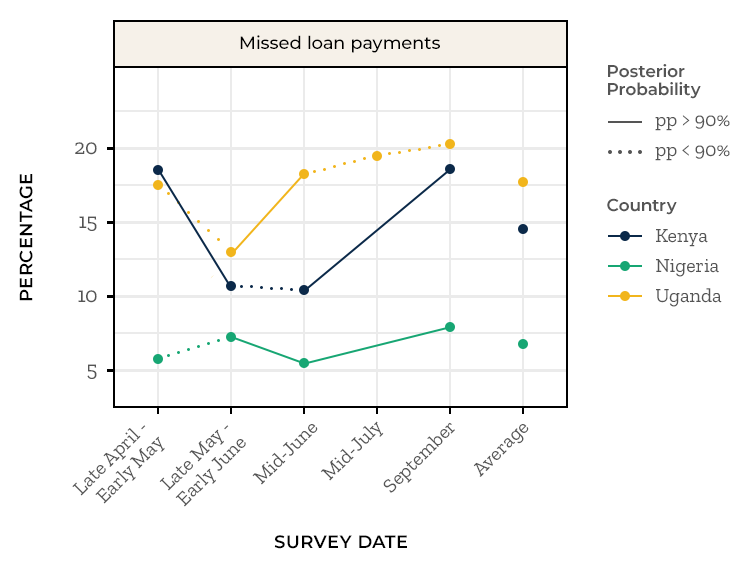

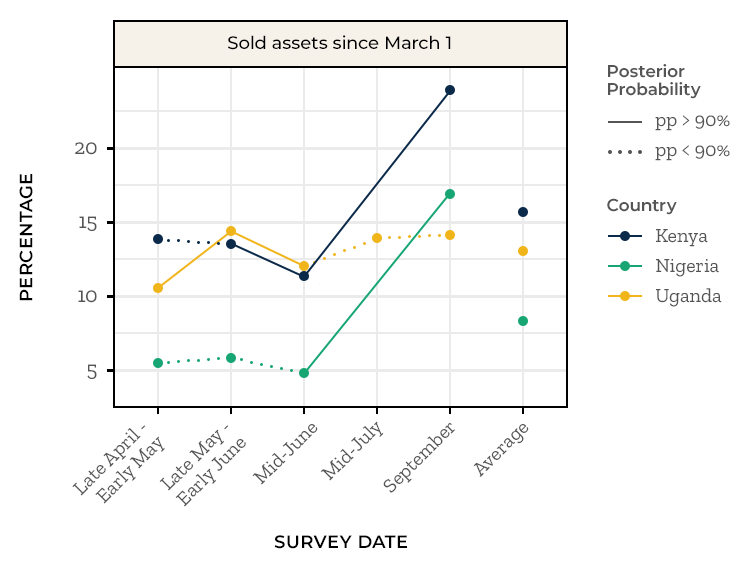

Financial insecurity measures over time

Note: Solid lines indicate that the difference between two waves has a posterior probability* greater than 90%; in other words, we can be 90% confident that the estimates in the two waves are different from one another.

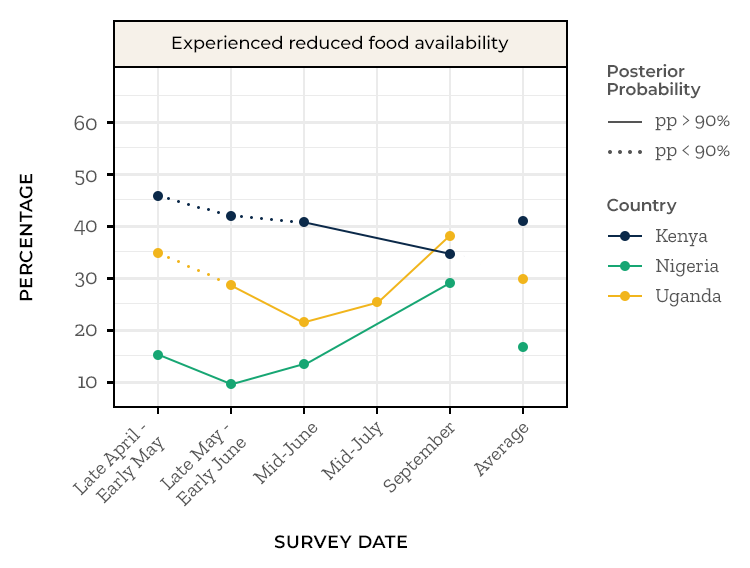

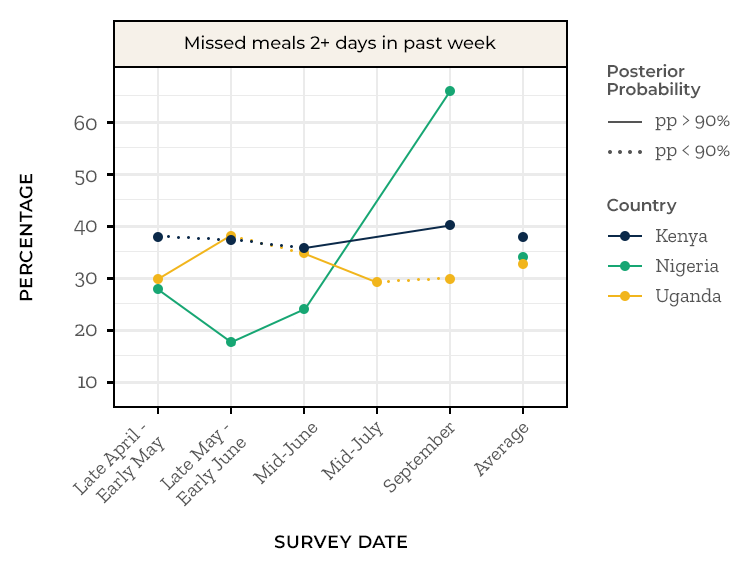

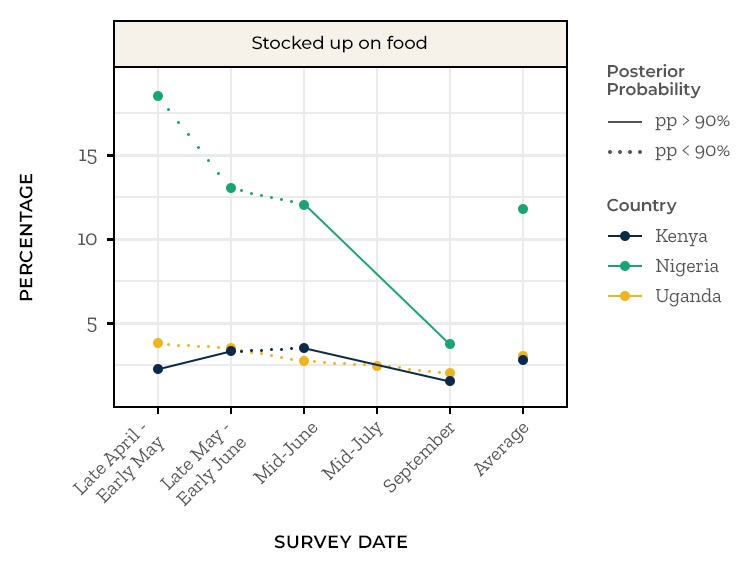

Food insecurity has also been high in these countries, with a substantial number of households reporting reduced food availability and the need to skip meals. Skipping meals has increased over time in Kenya and Nigeria, again suggesting increasing hardship as the pandemic has gone on. Stocking up on food as a coping mechanism is not very common and it has decreased over time. Food insecurity has been higher in rural areas; rural households were more likely to report skipping meals in Kenya and Uganda and more likely to report reduced food availability in Kenya and Nigeria.

Food insecurity measures over time

Note: Solid lines indicate that the difference between two waves has a posterior probability* greater than 90%; in other words, we can be 90% confident that the estimates in the two waves are different from one another.

How are households coping with economic shocks?

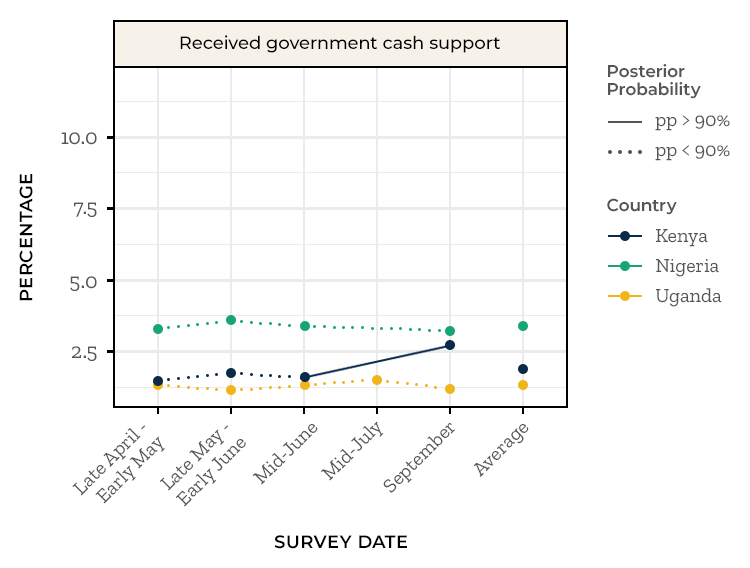

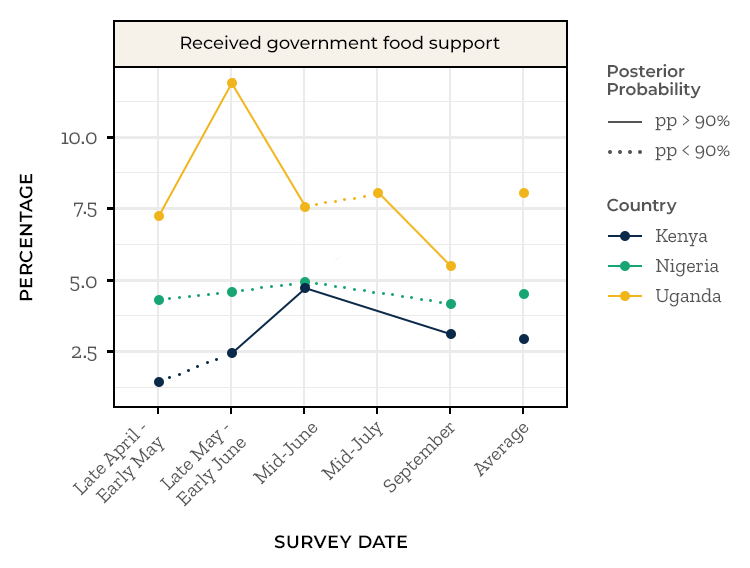

Despite evidence of significant economic hardship for households, very few have received any government support; almost none report receiving cash support and only a small share report receiving food support. Male-headed households in Nigeria and female-headed households in Kenya were more likely to receive support. With minimal government support, most households have to find their own coping mechanisms to get through the pandemic.

Percentage reporting receipt of government support

Note: Solid lines indicate that the difference between two waves has a posterior probability* greater than 90%; in other words, we can be 90% confident that the estimates in the two waves are different from one another.

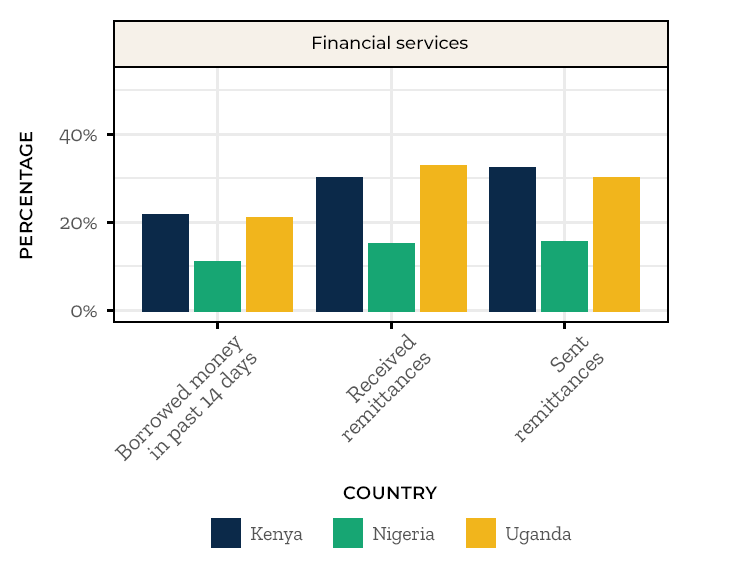

To understand how households are coping, we examined how households are paying for their living expenses. Many households have relied on financial services like loans and remittances that could provide a way to smooth the impacts of shocks. Nearly one-third of households in both Kenya and Uganda reported having sent or received remittances in the past two weeks, with approximately half as many households doing so in Nigeria. Borrowing was less common, with approximately 20 percent doing so in Kenya and Uganda and 10 percent in Nigeria.

Percentage reporting use of financial services

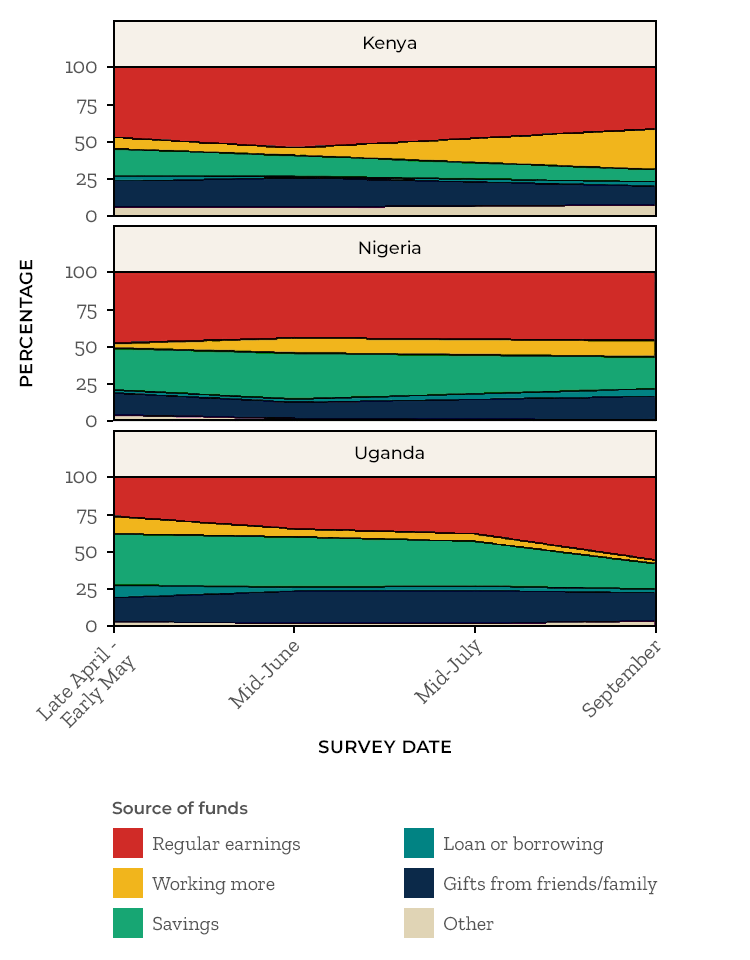

While more than half of households report having regular or extra earnings from work, many have had to rely primarily on savings or gifts from family and friends to cover their daily living expenses. Few have relied on borrowing as a primary source of living expenses, and the majority of loans that were reported came from family and friends rather than formal lenders. It appears that rather than rely on the government or the formal financial system, households have turned to their communities for support through the economic shocks they have faced, and evidence of both financial and food insecurity demonstrates that the existing support systems have, for many households, been insufficient to help them weather these shocks.

Primary source of living expenses

“To learn more about how households in Africa have been responding to and been impacted the COVID-19 pandemic, please read our other blog posts on the restrictions the pandemic has placed on households and on mitigating measures households are taking to reduce the spread of the virus between April and October of 2020.”

The data used in this blog is derived from the COVID-19 tracker phone survey that FinMark Trust is undertaking with GeoPoll in seven countries across sub-Saharan Africa. Mathematica provides analytical support to the project by cleaning and weighting the raw survey data to create nationally representative estimates; we then apply multilevel regression with post-stratification to enable analysis for subgroups of interest, such as women and rural populations. The survey includes about 75 questions and was administered periodically between April and October 2020.

*Our Bayesian analysis method produces estimates that account for uncertainty, which is expressed by posterior probabilities that describe the range of possible values for a given estimate. A posterior probability can be interpreted as the probability, given all the available information, that a certain outcome is different from a particular value or another outcome. For example, a posterior probability of 0.80 in the difference between outcomes for two groups can be interpreted as an 80 percent chance that the outcome is different for the two groups.