Direct clinical care services only accounts for a small part—an estimated 10 to 20 percent—of the factors that affect population health. The rest is determined by social, behavioral, and environmental factors, such as education, housing, and income, which interact dynamically to shape people’s health and well-being. These factors, which are sometimes called social determinants of health, play such an outsized role in keeping people healthy that a growing number of leaders in the government, philanthropic, nonprofit, and private-sector health care communities believe it is critical for providers to address them.

To improve patients’ overall health and well-being, we need better information about social determinants of health and the best ways to tackle them. This blog post is the fourth in a series that explores the needs, challenges, and opportunities related to collecting and using social determinants of health data to drive decisions in health care delivery and payment. Each post will examine these questions from the perspective of a different stakeholder group involved in such decision making. Click here to read the post introducing this blog series.

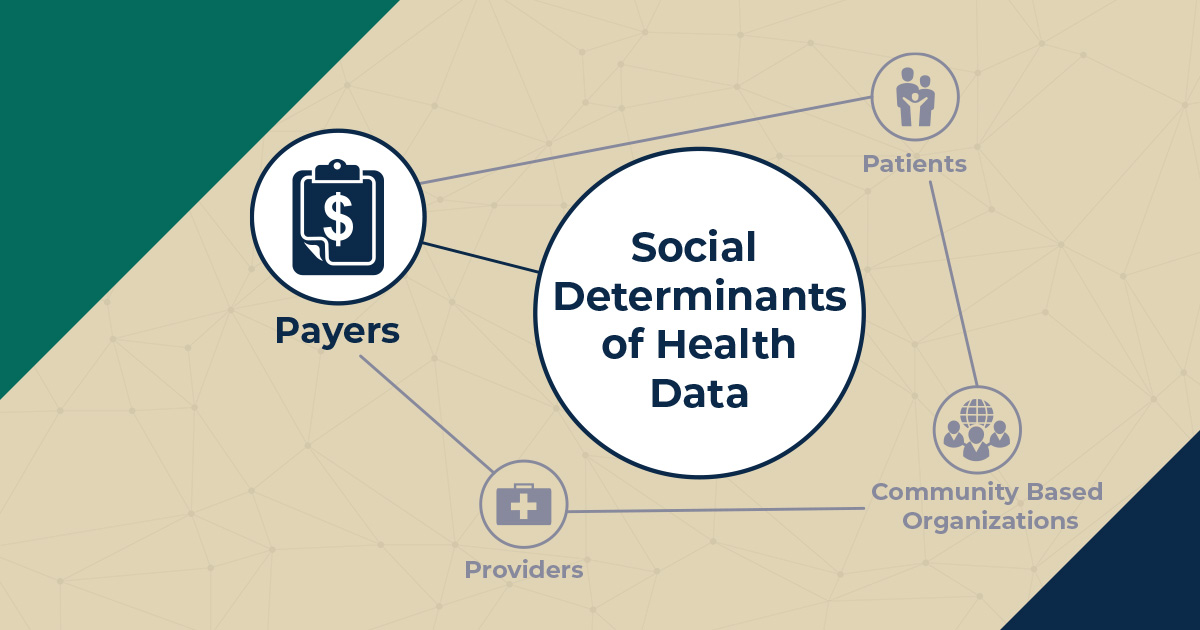

This post describes how both public and private health care payers are well positioned to foster and expand the collection and use of social determinants of health data across the health care sector.

From public insurers at the federal and state levels to private health plans purchased by employers, individuals, or government agencies, health care payers are responsible for improving the health of their members by financing the care they need. The long-term success and sustainability of a payer’s service model depends on its ability to anticipate and manage health care costs, and many payers are moving from reimbursing health care providers for the number of visits or procedures (fee for service) to paying for the outcomes of those services (value-based payment). As our colleagues noted in the previous post for this blog series, this shift has increased providers’ recognition of and efforts to address social determinants of health. Payers and self-funded employers, however, still retain much of the financial risk and are under great pressure to find new and better ways to control health care costs as health insurance premiums continue to rise.

Public and private payers can—and, in some cases, already do—play a central role in identifying and addressing social determinants of health. Many are experimenting with different approaches to meeting more diverse needs of patients, leveraging their ability to influence the larger health care system and improve the health of entire populations—not just individuals. This includes introducing new benefits, changing the incentives and expectations of providers, and creating partnerships with social service and community-based organizations. The success of these efforts, however, hinges on payers’ ability to identify individuals or groups who would benefit from receiving social services. To do this, many have begun to collect and use data on their members or beneficiaries to identify social needs with the greatest influence on health care outcomes and costs. For instance, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’s Accountable Health Communities Model requires participating organizations to collect and submit data on social needs and related community service referrals. The newly announced Integrated Care for Kids Model will do the same for pediatric populations, and some state Medicaid programs are working with their accountable care organizations to screen for and address social determinants of health. Kaiser Permanente launched its Thrive Local initiative after conducting a national survey that found respondents consider social needs to be just as important to their health as medical care, and UnitedHealthcare is partnering with the American Medical Association to standardize how social determinants of health data are collected, processed, and used.

With access to significant data and the ability to change payment structures and other provider incentives, payers are in a pivotal position to make and encourage health care decisions based on social determinants of health data. But to do this, they must overcome several barriers.

- Limits and inconsistency of existing data. To date, most social determinants of health data collected by the health care system are point-in-time social need data, collected through various survey and screening tools, or population-level data without individual identifiers. The tools used to collect individual data vary substantially across payers and initiatives. In addition, payers have access to little data on the use of social and community-based services and their downstream effects, including changes in social needs over time. The lack of universal standards for capturing and using social determinants of health data makes it difficult to identify best practices or scale promising pilot programs. Such standards will be even more critical if payers intend to use social determinants of health data to determine provider payments.

- Interoperability and data-sharing challenges. The ability to aggregate and share data across the health care system—commonly referred to as interoperability—is already important to public and private payers. Achieving interoperability becomes even more difficult, however, when including social determinants of health data in the shared health care data. This is in part because of the lack of standardization in social determinants of health data, but also because data sharing must cross service sectors. As our colleagues described in their post about community-based organizations, partnerships between health care and community service providers would be greatly enhanced if they involved seamless exchange of patient information, including information about identified social needs and referrals to and use of social services. Unfortunately, negotiating data-use agreements and data-sharing procedures between these entities is complex and challenging.

- Limited resources and funding silos. The movement toward value-based care has pumped billions of dollars into the health care system to collect data on and address social determinants of health, sparking innovation and new data-driven technologies. Yet, many of these investments are payer specific, limiting their benefits to certain social determinants, geographic areas, and populations. In some regions, the concurrent efforts of multiple payers have created duplicative and inconsistent requirements that add inefficiencies, rather than value, to social determinants of health data collection efforts. Furthermore, the social service sector lacks comparable investments, and many community-based organizations do not have dedicated funding streams, relying instead on grants and donations to deliver their core services. The patchwork funding structure of social services does not incentivize cross-sector innovation or data infrastructure development.

Fortunately, payers have big opportunities to advance the goal of leveraging social determinants of health data for health care decision making.

- When possible, align data requirements and measures across payers. Looking for ways to build off of what has already been established will increase the efficiency and maximize the consistency of social determinants of health data. For instance, The Social Interventions Research and Evaluation Network’s Gravity Project will identify common data elements and value sets to encourage consistent and harmonious data collection on food security, housing stability and quality, and transportation access. When introducing new data collection requirements or standards, payers should still be sensitive to cultural or community-level differences that may necessitate flexibility—for instance, in the exact screening instrument used, or even the language used to talk about a particular social determinant. Payers should also look for opportunities to align and coordinate with health care providers and systems within their network, as well as other payers in their region, and seek chances to partner with community and social service organizations to reduce duplication and increase the usefulness of the data that are collected.

- Work across sectors to identify and test novel solutions. Payers don’t need to try to tackle social determinants of health data collection and data-driven decision making on their own—social services agencies, governments, foundations, and coalitions have a wealth of knowledge about what works and the ways in which interventions need to be adapted to align with the cultural and environmental factors that influence their effectiveness. Approaching these initiatives iteratively, with plenty of opportunities for testing and refinement, will lead to the best solutions that are most likely to accomplish the desired outcomes. Investing time to establish productive partnerships will help payers supplement their in-house expertise and introduce opportunities to have a bigger influence than they would be able to achieve on their own. There are many promising cross-sector initiatives, such as West Side United in Chicago and Humana’s Community Partnership program.

- Build for the future, not just for today. Payers should invest in the infrastructure necessary to measure and meet the many social needs of their members, including expanding health information technology and data analytic capacity, implementing broad staff training, and creating organizational partnerships. For instance, payers can expand their analytic teams to include staff with experience manipulating and applying different social determinants of health data sources, or payers can collaborate with community and social service partners that serve multiple functions within their communities. Creating or facilitating access to technologies that support collecting and using social determinants of health data, such as the Unite Us platform, can support providers in the transition to value-based arrangements and increase the chances that such payment models accomplish the meaningful effects desired.

By using data to determine where to act, how to change, and when to scale, payers have the opportunity to build or foster the programs and systems capable of making a big impact on social determinants of health, and improve their bottom line in the process. To take full advantage of the opportunity, payers need to rethink what health care means, who it includes, and the role it plays in improving the health of individuals and populations. Doing so has the potential to improve the health not just of their members but also of entire communities—and the health care system itself.

Read other posts in this series:

- Lost in Translation: The Importance of Social Determinants of Health Data from the Patient Perspective

- The Power of a Data-Informed Partnership: Working with Community-Based Organizations to Address Social Determinants of Health

- Prescribing Social Services: Leveraging Data to Diagnose and Treat the Social Determinants That Affect Health

- To Address the Social Determinants of Health, Start with the Data