The lack of transparency in health care pricing is one of the barriers to reining in rising costs. Greater transparency has the potential to lower prices for many services by promoting competition and improving oversight of health insurance issuers and plans. This is the case even when consumers don’t price shop. Under the transparency provisions in the Affordable Care Act, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services finalized the hospital transparency rule in November 2019 that required hospitals to publish standard charge information based on negotiated rates starting in 2021. More recently, the Transparency in Coverage (TiC) final rule went into effect in July 2022, requiring that health plans and insurance issuers do the following:

(1) Make available to enrollees an internet-based, real-time cost estimator that provides personalized out-of-pocket cost information with underlying negotiated rates (prices that doctors and hospitals negotiate with insurance companies)

(2) Make available to the public machine-readable files that show negotiated rates and allowed amounts for all covered items and services. The intent of these requirements is to support individual consumers and other health care purchasers by making price information publicly available.

The TiC rule quickly made an industry-wide impact—nearly 100 percent of payers have published their price data as of early 2023, resulting in the release of billions of price records to the public. Despite the early excitement, however, data innovators and researchers find themselves grappling with enormous, messy data files and confusing rate patterns. Meanwhile, consumer awareness of the new price transparency data remains low—and thus there is still a long way to go before these data can help make the health care system more competitive and drive down prices. Price transparency gained attention during the recent U.S. Senate Committee on Finance hearing on “Consolidation and Corporate Ownership in Health Care: Trends and Impacts on Access, Quality, and Costs,” where several witnesses noted that improving access to and the quality of price transparency data is a necessary next step to unleashing the market power of consumers and purchasers.

Federal policymakers can play a significant role in making progress toward greater and more accessible price transparency. Based on Mathematica’s extensive work integrating, analyzing, and interpreting price transparency data, we’ve put together the following recommendations for lawmakers looking to improve the usability of payer price data. Notably, data requirements established by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) dictate what data plans report and how they report them, affecting the accessibility and usability of these data. With this in mind, lawmakers should focus on needed improvements, and provide administrative departments adequate flexibility to implement the requirements.

- Capture both facility and professional fees in the cost estimator to help consumers understand the total costs of treatment.

Many outpatient services can be provided in more than one care setting, and the choice of care setting has implications for patients’ out-of-pocket costs. When care is delivered in a facility such as a hospital outpatient department or an ambulatory surgical center (ASC), health plans make separate payments to the facility and the medical professional delivering the care. However, we’ve found that commercial plans pay higher facility fees to hospitals than to ASCs. We also know that the price of care in a doctor’s office is usually lower than the total price of the same care at a hospital. To ensure that consumers understand how much they will actually pay for care, policymakers should require that cost estimator tools provided by health plans display both professional fees and facility fees for facility-based providers.

- Strengthen requirements to help plans report accurate rates.

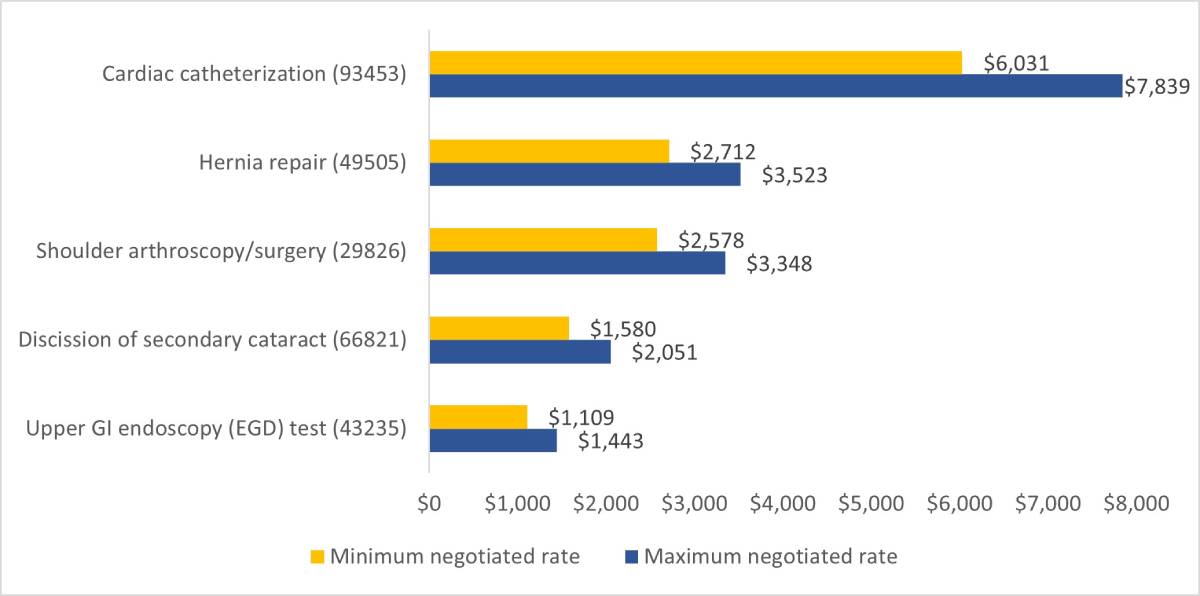

A major limitation of current plan price data is that providers can have different rates for the same plans and services. In the example below, a hospital’s prices for cardiac catheterization range from $6,031 to $7,839. Which rate is true? We cannot accurately compare rates for a service across providers in the market when rates are not unique by provider. - Add network types to data to enable cross-plan comparisons.

The current price data do not specify plans’ network types (for example, health maintenance organization [HMO], preferred provider organization [PPO], point of service) in any data fields. It is important for data users to distinguish plans’ network type when assessing price variations. In some cases, a given provider might be contracted with a payer’s HMO network but not its PPO network; in other cases, the provider might negotiate different prices for the payer’s HMO and PPO networks. Without accurate information on provider networks, analyses of rate differentials across payers and plans might yield misleading results. For example, a data user might mistakenly compare the price of a service under Issuer A’s PPO plan to the price under Issuer B’s HMO instead of Issuer B’s PPO. Currently, researchers identify plans’ networks by linking the standard 14-digit Health Insurance and Oversight System (HIOS) IDs to external data sets. But this is far from ideal, as only 6 percent of all plans reported so far have HIOS IDs, and network information is still lacking for most plans identified by using employer identification numbers. Having CMS require a data field that indicates each plan’s network type will greatly enhance the usability of the plan price data.

- Confront the zombies to reduce data redundancy.

Researchers found that the majority of reported prices are in fact so-called “zombie rates” that are of little practical use. For example, an obstetrician/gynecologist might be listed with colonoscopy rates in the price data, having never provided such services. This is not surprising, as plans set fee schedules for many physicians and clinicians regardless of their specialty (consider Medicare’s physician fee schedule that applies to all physicians in the nation). Large numbers of redundant rates obscure the true distribution of rates across providers and plans and significantly inflate the size of the data. Mathematica, along with other innovators, is supplementing price data with claims data to eliminate zombie rates, but this issue can be more effectively addressed through data standardization. Policymakers should consider adding a required data field that would flag providers with fewer than 20 claims for a given service in the past year. This would be similar to the current requirement for the allowed-amount machine-readable file. Alternatively, policymakers can ask plans to upload a crosswalk of providers and procedures that have 20 or more claims in the past year. Both approaches would enable data users to weed out zombie rates without significantly changing the current data file structure.

- Establish monitor processes to ensure data accuracy and validity.

Although nearly all payers published their price data within six months of the launch of the federal mandate, our analysis revealed several potential issues with the validity of plan price data. In addition to the issues mentioned above, we have observed extreme price variation (for the same service covered by the same plan, the highest price is more than 10 times of the lowest price), invalid data values (such as non-existing billing code type), and rates associated with expired billing codes (such as MS-DRG [Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Groups] version 36, effective prior to 2020). To help data users make meaningful use of price transparency data, policymakers should establish a process to monitor the accuracy and validity of information disclosed by plans, using CMS to fill in detailed requirements. One way to establish the process is to partner with states on monitoring efforts. Given their established connections with local insurance issuers, state insurance departments could be more effective than the federal government in exercising enforcement powers to improve the accessibility and usability of the plan price data. High-quality price data would in turn help these departments support broader initiatives and facilitate health care decisions within the state. The data can also inform the implementing of state-level cost growth benchmarks, aid in the monitoring of anti-competitive contracting practices, and help state regulators understand the drivers of premium increases during the annual rate review process.

Rates for the same outpatient procedure under the same plan vary, even at the same hospital.

Source: Mathematica Payer Price Analytic Database. Raw data come from one national payer’s data release in April 2023.

This widespread issue in payer data suggests that current data requirements might be missing important variables that payers use to determine their rates. Requirements that ensure the uniqueness of rates will greatly increase the usefulness of payer data. For example, the type of bill, which indicates the type of facility and type of care for a given service, is an important field that health plans, including Medicare, use to determine payments on institutional claims. However, such information is omitted from the CMS’s data requirements, and thus missing from the payer data. To improve data accuracy, policymakers should instruct plans to include an additional required field for type of bill or provide payers with instructions to report information in an existing required field.

It is common in outpatient services, such as radiation oncology, for specific revenue codes to be included on claims to determine the rate for a procedure code. However, the current data requirements do not allow plans to report combinations of billing codes that determine a rate. Although different plans may have different pricing rules, policymakers should require plans to report unique rates while allowing them to include multiple billing code fields.

The industry is still in the early stage of developing solutions around the new price transparency information. Relevant, easy-to-access pricing data will eventually influence consumer behaviors and how payers and providers negotiate contracts. However, the health care system is complex, and the pricing of health care services is no different. We believe that there is opportunity to improve the usability of price transparency data through improved policies – a sentiment that is shared by philanthropy, doctors, businesses, and patients. By setting clear requirements and effectively enforcing them, the federal government can enable health care innovators adopting price transparency data into impactful technologies.