Teacher recruitment and retention challenges have increased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. But even before that, students of diverse backgrounds have historically not seen themselves reflected in the adults in their classrooms and schools. Why does this matter? Students of color do better in school when they have teachers who share similar identities. For example, Black students with at least one Black teacher in grades K-3 are 13 percent more likely to graduate high school and 19 percent more likely to enroll in college than their same-race same-school peers. And all students benefit from diversity of the teacher workforce: teachers of color are positive role models for all students in breaking down negative stereotypes and preparing students to live and work in a multiracial society.

This episode of On the Evidence focuses on efforts to diversify the teacher workforce and provide supports to teachers from diverse backgrounds in schools. The guests for this episode are Colorado State Representative Jennifer Bacon; Janet Damon, a teacher at Delta High School, in Denver, Colorado; and Steven Malick, a senior researcher at Mathematica.

Colorado State Representative Jennifer Bacon is Assistant Majority Leader and represents House District 7, which includes the Denver International Airport and Denver’s far northeast neighborhoods. Representative Bacon serves as Vice Chair of the House Judiciary Committee and a member of the House Education Committee. Representative Bacon is also the Chair of the Black Democratic Legislative Caucus of Colorado.

Janet Rene Damon, Ed.S. has spent 24 years as a high school teacher, digital librarian, and literacy engagement activist. She is co-founder of Afros and Books, a citywide literacy and nature engagement that offers culturally sustaining programming and book clubs for families in Denver. Janet was awarded the Inaugural Making our Futures Brighter Award from the Black Family Advisory Council in 2022, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Humanitarian Award in 2022, and the Library Journal Mover and Shaker Award in 2020.

Steven Malick of Mathematica focuses on bridging the gap between research and practice in the K–12 education system. He specializes in working with districts, states, and other organizations to understand and apply evidence in service of improving educator effectiveness and student achievement. His work has helped clients increase the diversity of the teacher workforce, develop social-emotional competencies in children, and accelerate implementation of research-based strategies.

Watch the episode below or listen on SoundCloud here.

View transcript

[Rep. Jennifer Bacon]

In 2023 we have found it's not as simple as putting questions in front of a child, and figuring out how much they know. It is much more multifaceted than that. The conversations about curriculum are not just about, you know, what is actually in the textbook. It is also about who is delivering it. All of these conversations have very serious implications to who's teaching and the diversity of those who are teaching.

[Rick Stoddard]

I’m Rick Stoddard from Mathematica, sitting in for J.B. Wogan, and welcome back to On the Evidence.

On this episode, we focus on efforts to diversify the teacher workforce and provide supports to teachers from diverse backgrounds in schools.

Teacher recruitment and retention challenges have increased since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. But even before that, students of diverse backgrounds—historically—have not seen themselves reflected in the adults in their classrooms and schools.

Why does this matter? Students of color do better in school when they have teachers who share similar identities. For example, Black students with at least one Black teacher in grades K-3 are 13 percent more likely to graduate high school and 19 percent more likely to enroll in college than their same-race same-school peers. And all students benefit from diversity of the teacher workforce: teachers of color are positive role models for all students in breaking down negative stereotypes and preparing students to live and work in a multiracial society.

To help us better understand these issues, efforts, and challenges, our guests for this episode are Colorado State Representative Jennifer Bacon; Janet Damon, a teacher at Delta High School, in Denver, Colorado; and Steven Malick, a senior researcher at Mathematica. My colleague, Kirsten Miller, a Senior Communications Specialist here at Mathematica, leads this episode in her On the Evidence debut.

We hope you enjoy this conversation.

[Kirsten Miller]

Thank you, Representative Bacon, Janet, and Steve, for joining us for our teacher diversity On the Evidence podcast. So we know that teacher recruitment and retention challenges have increased as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. But even before that, for students of diverse backgrounds, we've seen a shortage of diverse teachers. So, Steve, I'm going to ask you to kick us off by explaining a bit about why it's important for children to see themselves reflected in the adults in their classrooms and schools.

[Steven Malick]

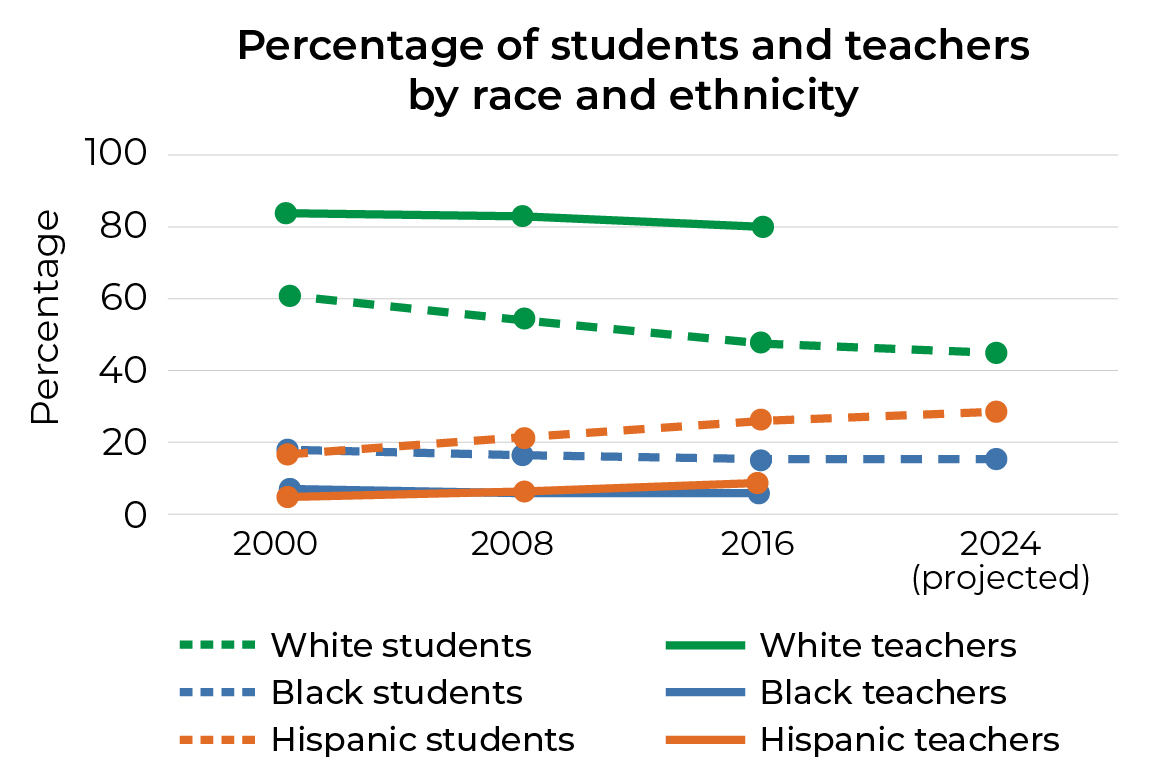

Thank you for having me. And it's great to meet you, Representative Bacon, and Janet. And, actually, I might even like pivot just for a second and ask us to be specific. When we use the word diverse, are we're using the term as a code word for racial and ethnic diversity? Everyone brings lines of identity that are unique. But particularly in the education system, we see that the workforce is predominantly White folk and women, right. And so we can talk about diversity in a lot of ways. But I think, in particular, diversity, racial and ethnic diversity being reflective of the student population is going to be critical. In reality, all students benefit from having teachers of all sorts of different backgrounds. We also know that students of color benefit particularly from having teachers of color.

Now, the evidence isn't necessarily like a randomized controlled trial comparison group design, but we have some good correlational analyses that point to students of color doing better when they have at least one teacher of color who shares that line of identity. And there's a lot of hypotheses for why this is. One is, you know, kids see themselves in their teachers. And they see, you know, an adult who they can admire and value as a role model. And role models play an important role in formation. There's also this idea that, you know, if you're a teacher of color, you might operate in more culturally responsive ways, able to connect with your kids and help make the content really accessible to them. And I think importantly, you know, I'm a former public school teacher myself. I taught in New Jersey and in New York City. And bias, whether explicit or implicit, plays out in lots of nefarious ways in the classroom. And I think it often plays out with the White adults in the classroom when they have teachers of color -- or, excuse me, with students of color in ways that sometimes are unexpected or even, you know, not even aware of, whereas, you know, if you have a teacher of color, they are less likely to have an implicit bias that holds low expectations for the possibilities of kids. So -- and that plays out in a lot of different ways. I can keep going on and on. There's a lot of interesting research out there. But I'd love to hear what others have to say about that, too.

[Kirsten Miller]

Thank you so much, Steve. I think we'll turn to Janet next and just, you know, Janet, as a teacher, as a librarian, as a literacy expert, is what Steve is describing lining up with what you've seen in the classroom and in your school?

[Janet Damon]

One of the things I think about, you know, this is my 26th year in education as a teacher and I have used and experience a lot of different roles. And one thing I think is that students do sometimes experience some implicit bias. And sometimes, you know, I've had students tell me that they've had teachers who necessarily didn't show them the kind of care, the kind of respect, the kind of affinity that made them feel very welcome. I've had students who have a lot of intersectional identities so students who might be from different cultural backgrounds, different faiths, different gender identities, different sexual orientations. And sometimes, you know, we see this sort of, you know, space where students get to feel unseen, unheard, unvalidated. And that reduces their likelihood of wanting to stay an active participant, to show all of their self, you know. When we are seeing students spend cognitive energy trying to make sure that they are not being targeted in the classroom, whether by students or whether by their teacher, then that's reducing the amount that they're able to use all of that cognitive power for the curriculum, the content from radical imagining.

So I think that, you know, over the course of time, these experiences also are cumulative for students. So students who experienced bias in elementary or kinder or 1st or 2nd grade, how likely do they feel engaged, you know, over the course of their instructional journey? So we have to think about the work that we're doing as being sort of cumulative, and building upon the experiences. And also, the work that I do as a high school, I teach at a pathway school that supports students who have experienced a number of different life experiences that can be challenging. Many of them work. Many of them, you know, have families that they help and they support. Many of them have had experiences where they might have had a family member who was incarcerated. So when we think about the healing work that a teacher can do, I also take that responsibility that I need to make up for some of the experiences you may have had with a teacher that weren't positive. So thinking about our role is interlocking and over the course of time.

[Kirsten Miller]

Thanks so much for that, Janet. And now I'd like to turn to Representative Bacon. And Representative Bacon, as a member of the Education Committee for the Colorado General Assembly, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about whether teacher diversity is a concern in Colorado and if there are any specific metrics that you and your colleagues are monitoring to gauge the health of teacher diversity in your state.

[Rep. Jennifer Bacon] Thank you. That's such a great question. Also, I just want to give praises to Janet who has saved lives with her work, and she has certainly saved mine. So I will take any platform to say that. But yes. I mean, the way that we talk about teacher diversity has been direct and indirect. I can say even before I was in the legislature, I was part of a teacher diversity recruitment task force in a bill that was passed in 2012. And the data that we found after the study, particularly in thinking about teacher pathways, was that in the entire state in formal education programs, there were only 36 Black candidates. And, you know, Denver Public Schools has 4000 teachers alone, just in one district. And so I know for the last ten years it's certainly been of interest, particularly to legislators of color. And I will say the last teacher diversity recruitment and investigatory bill was probably even two or three years ago brought by a member of the Black Caucus. And so we believe teacher diversity is important for the things that we heard from, from our two colleagues here just a moment ago. But, also, it's a key part of the system.

You know, if we go all the way back to Brown v. Board and those suite of cases, if you recall, there was the doll study, right, where do kids see themselves reflected based off of what we're teaching? The conversations about curriculum are not just about, you know, what is actually in the textbook. It is also about who is delivering it and what kind of context they could provide. The conversations around assessment and the cultural responsiveness of the questions, let alone the outcomes and quote, unquote academic gaps, you know, all of these conversations have very serious implications to who's teaching and the diversity of those who are teaching. So directly we will look at the teacher pool.

And indirectly, we look at these outcomes and really try to find root causes, especially because we create, we continue to create systems to quote, unquote assess children, right. And I think in 2023 we have found it's not as simple as putting questions in front of a child, and figuring out how much they know. It is much more multifaceted than that. And so every time we have conversations, we talk about who's teaching, whether it is funding math; after school tutor, tutoring programs; to the assessment to literally licensure. There are people who, such as myself, who regularly ask about those questions because it plays such an integral role. Who's in front of kids plays such an integral role in the outcomes that we all are talking about.

[Kirsten Miller]

Thank you so much, Representative Bacon. And we have one of those teachers with us today. We have one of those teachers who's in front of kids. So I wonder, Janet, if I could ask you to share your story about how you became a teacher, how you entered the education field?

[Janet Damon]

Well, I'll share that, you know, I come -- I'm very blessed to have a father who, when you talk about families and parents as the first teacher, that really was my first teacher. My dad every summer would give me space to research things that I was interested in. He would take me to the library. I would do these reports over the summer. And then, at the end of summer, he'd have like a special time like a dinner that he would ask me everything I learned. He'd asked me questions about it. He was just so excited for me to explore the world. And so my dad is a very curious person.

The other person who really made an impact on me was my 2nd grade teacher, Miss Graham, and she just adored me. I was in Louisiana. I was in New Orleans and at a parish school. And she -- my mother used to crochet for me little dresses, and I was wearing like a yellow one. And she said, You have on this most beautiful handmade dress! Oh, this is so important. You don't have to sit on the carpet today. You get to sit in a chair. She used to love to hear me read out loud. And so I just won't ever forget how much she loved me.

And it was really important to me because the next year, when I went to 3rd grade, I came to a very small neighborhood, here in Denver, Colorado. It was kind of in a rural part of the state. My dad hadn't really gotten his bearings yet. And, when I went there, I had a totally different experience. I had a teacher who really -- I have my students who are transitioning to lunch, as well, so you guys can go ahead and go. And that teacher, I was the only African-American girl in the school. And when I was in her class, she wouldn't take me to specials. She would leave me in the classroom alone with coloring sheets and handouts. And almost I felt so excluded, so marginalized. And I hold up both of those teachers as being the reason why I became a teacher. One was to make sure that students felt loved, seen, heard supported; and the other was to make sure students didn't feel marginalized and excluded.

[Kirsten Miller]

So, Janet, I'm sorry. I know your students are transitioning, but I do have a follow-up question for you. Were there challenges? And, if so, what challenges did you face when you were looking for a teaching position? And in your -- in your area preparation as well?

[Janet Damon]

Well, you know, I ran into barriers around teacher preparation. So I knew I wanted to be a teacher. I loved my students, and I ended up going to MSU to become a teacher. And when it came time for the student teaching portion, I really felt I could not go that duration of time without having an income. So I took up my second love. And I also love books and love reading, and so I became a librarian. And so, with me, I was very fortunate that at the time, there were some shortages of, you know, people to work in high schools to be able to teach research and to teach. And so they offered me a program where I was able to get an emergency authorization. I was able to go into the classroom and complete my teacher student teaching portion while taking courses and while working in a school. So that kind of innovative programming made a space for me. And that allowed me -- can you shut my door, too, baby -- that allowed me to be able to not only not only become an educator but allowed me to also be able to support my family, help my family. I had a nontraditional pathway. But it also gives students access to someone who had -- you know, I have an advanced degree beyond my master's. I have my master's degree, I have lived experience that matches my students. I come from a family -- my mother's an immigrant. My mother's from Korea. My father, you know, grew up during Jim Crow segregation. So all of those experiences inform what I bring to the classroom, especially with multilingual learners, with students who have encountered barriers regarding, you know, income disproportionality. And so all of that lends itself to what I bring to the classroom.

[Steven Malick]

When Janet talks about the challenges of getting in, the barriers of entering the workforce, the teacher workforce are really pronounced. And I think this is one of the big issues that the education space really needs to grapple with. You know, I think rightly so, there has been a big push toward making sure that teachers have the content expertise and preparation needed to be teachers. Our kids deserve the best, period. Nonnegotiable, right? Like, all of our kids deserve the best. But we've sometimes, you know, hung our hat on barriers to entry that really don't -- on sorts of things that really don't get very far. Licensure, licensure exams don't necessarily predict teacher quality, right? So if we're saying everyone has to pass this test at a certain, you know, score, that might not actually have anything to do eventually with the quality of teaching that happens in that teacher's classroom.

And then, Janet, you also talked about just the expenses, right? Like, that's super tough, right? That's true of a lot of folks. If you go into just about any school and you interact with some of the paraprofessionals that work in that building, many of them will say, yeah. I really wanted to be a teacher. But for one reason or another getting that four-year degree or getting that teacher certification because of cost just wasn't feasible for me. And so you see a lot of school districts that are kind of being innovative with paraprofessional pipelines. But every single paraprofessional has, like, kind of their own stuff they've got to work through in terms of like credits and other sorts of requirements.

So I think it really invites policymakers to think about what are really the things that we have to hold as nonnegotiable, that we really think are linked to teachers doing right by kids, particularly kids who have been historically and I would argue purposely underserved by the education system and setting up systems around that.

But, you know, Representative Bacon, you mentioned the number of candidates of color, I believe, in the pipeline in Colorado. And that's true nationwide. And I'm a little fuzzy on the exact number right now. But they did a study of in Pennsylvania, of the number of Black men in the pipeline to become teachers. And it was maybe in double digits. It might have been around 100. The entire state of Pennsylvania, one of the most diverse states in the country, right, like, what? Huh? What? That doesn't make sense, right. And so, you know, I think it also underlies there's this structural issue that many educator prep programs face, which is it's a model of, if you build it, they will come. If I have this fancy program that's geared towards Black men or, you know, we're trying to get more queer educators in the door or whoever, right? If we just build it, magically, the candidates will apply. And, like, our institutes of higher education reflect that. So they have a separate admissions office. They have a separate department of education, all that stuff, right? Well, that's not how it works. Like, I don't need a fancy study to tell me that, if I'm not talking to folks of color about becoming teachers, they're not going to show up at the door coming knocking. Like, we need to actually, like, we as a system, as a society need to be reincentivizing the profession of education and talking to prospective candidates, particularly prospective candidates of color to get them in the door, understand their unique needs and challenges because racism as a system has put people in situations which makes it trickier to get what they -- get where they want to go, right, and figure out ways to remove those obstacles. But let me stop rambling because, Janet, I think I see you wanted to react.

[Janet Damon]

I was just affirming. I was just affirming there was a lot of -- a lot of just great nuggets that you shared there. So that's all I have.

[Kirsten Miller]

So I would love to hear from Representative Bacon on this around those policy implications and around anything that Colorado may be doing, for example, around a teacher apprenticeship program or around the teacher pipeline issues or, you know, around what Janet had mentioned where so many student teachers don't have the luxury of having what is essentially an unpaid internship. So I'm wondering if you can speak to that, Representative Bacon.

[Rep. Jennifer Bacon]

I think that it's -- before being the legislature, I was on the Denver Public School Board. And before that I actually worked for Teach for America. So I've got a few thoughts on a lot of some of these things, especially over the last ten years. I will say that -- and this may sound kind of cynical, you know, the education committee is factually filled with educators. You know, I've taught. I think the chair of education committee was a teacher. Four other teachers at least on the Democratic side. And so the topic is always of interest. I think our challenge has been making policies that are sustainable and coherent, you know.

So for -- as I mentioned in my first remarks, I would say in the last ten years, every three years there has been a teacher of color recruitment or diversity investigation type of bill. And as much as that demonstrates there's an interest, it also demonstrates that we have not done something sustainable that, therefore, we need to bring another bill, you know. I think something that's always at top of mind, particularly here in Colorado, is just quite honestly the funding of public education. It is some of the worst funding formulas in the country we have here in Colorado, particularly given our cost of living and what quite everyone else can see with their eyes in regards to how much things cost, what kind of future they want and whatnot.

And then, when we talk about teacher pay and then, quite honestly, teacher pay for kids of color who also borrow at the highest rates in America, right, these are the types of things that we have to talk about beyond just saying, Hey, we need more teachers of color, you know. And, again, so just to reiterate, you know, we do have apprenticeship programs. We have them at district levels. The state has typically funded grants or pilots. We have made legislatively the pathways for someone to qualify as an apprentice, you know what I'm saying, and work study to become a teacher. But the funding isn't consistent, right? Or we haven't seen statewide or state-prioritized-led initiatives. There have certainly been like, teach -- you know, all of these types of things that go out there, but it hasn't been seen -- it hasn't become a statewide priority. And you can always tell what's a priority by what the state funds, right. Our budgets are moral documents, if you will.

So I think also what we see right now, you know, I'm spending a lot of time because districts are trying to figure it out for themselves. We're seeing a huge proliferation of CTE programming, right career and technical education programming, which licensure is actually different, and hands-on is actually different. We're seeing school districts share teachers in the rural parts of the state. We're seeing the metro districts doing -- you know, Denver Public Schools has its own teacher apprenticeship program and pipeline that they support and fund within, you know, our district. The rural public schools will do that too. But school districts are being left to kind of figure out the most of this because, even though we may have an apprenticeship program, if it's not in the right subject matter, right, or if they can't get to the part of the state or if they can't actually fund it sustainably, it doesn't really matter.

So, again, the conversations we have at the state level have to be -- you know, we have to pull back those layers of that onion to be able to figure out what we're doing by way of root cause. But we also need to be proactive and show initiative to continue to connect those dots and to elevate it to where things are, again, sustainable.

[Kirsten Miller]

Thanks so much for that explanation, Representative Bacon. And I'm going to give both Steve and Janet a chance to respond to that and see if there any, anything that you'd like to share.

[Janet Damon]

Well, I will say what I think, you know -- you know, there's so much that Representative Bacon shared just in terms of the funding and the prioritization, you know. And I think, you know, looking at it both from a macro level but also this micro level, something I've seen over time is also the -- you know, the interactions and the way that people are treated. Like, every organization begins to build its own sort of stories that are told about that organization. And so, you know, I work for a public school district that, you know, a lot of times, educators of color feel that they're not really being retained.

So part of the story is this idea of recruitment, how do we get people in the door. But I've seen recruitment work really well. I've seen people -- you know, we've had folks go out and recruit people from the South or recruit people from the East Coast or recruit people from all over, you know, bring them and encourage them to come here to Denver, Colorado. And then one of the things that I did for many years is I helped to support an affinity group for our educators of color, for predominantly women of color. And the stories of how they were treated once they got into these buildings. So when you tell me that a school has one or none, there's a story there. There's a lot of painful stories there. And so I have, you know, just now -- at some point, I was starting to get calls with people whose mental health was literally being impacted by the levels of macro and microaggressions. You know, one, you know, teacher called me because the principal -- she had told students not to use the N slur, and this principal left a note on her desk saying, you know, that we don't discipline students on the words that they use, the language that they use. And, again, an academic article, you know.

Or I've had someone who called, and they were feeling so much anxiety about going to work the next day because of some of the ways they were pulled out of their teaching role and told that they're going to be doing discipline for the rest of the year because they're better at it. And so this was someone who had a PhD in music and was there to teach music, and now they were, like, you're the restorative justice person.

And so there are times where I just tell people, you know, what you need right now is to be whole and to be -- your mental health will come first. And so now I -- I keep a therapist on my phone dial, and I route people to her who I feel are having, you know, an immediate need. And so, you know, I think -- we can think about recruitment a lot. But if we're harming people in the process of trying to get our numbers to look a certain way, then the damage we're doing is deeper and long-lasting than, you know, we anticipate, I think.

[Rep. Jennifer Bacon]

I just want to echo what Janet was sharing. And having sat at a local- and state-level policy table, you know, at the local level, we certainly realized our levers. You know, the data, to her point, it's in every level of the district. I mean, don't even get me started on what it means. We have seen data that from people who are managed by women of color, right, or evaluated by women of color, and particularly Black women, those things are often -- so, I mean, I remember being at the district and saying we need to make our own management and accountability systems retention and looking at this data because, otherwise, the culture, which is reinforced by system, right, it's not going to get us there.

And, at the state level, we, it's interesting to talk about it. And the only way it kind of comes up is through accountability system or standard, right, and that is either through licensure or through assessment or even school performance. But, for what it's worth, it comes up every once in a while. Like maybe retention of people of color would be increased if we measured that and evaluated your school district on it. And we don't. I mean, don't get me started. We could talk about evaluation systems and what that really means for kids and their spirit. But for the system that we have, we don't use it towards these outcomes. And, yet, we keep talking about it as a priority. And so I just wanted to throw that out there to echo what she's saying because recruitment does not -- I'm sorry. Recruitment gets most of the attention, but retention does not get policy attention other than perhaps pay, right? So just wanted to throw that out there and say thank you, Janet, for sharing.

[Steven Malick]

And one of the things we see play out is when people share stories of, for instance, the Black male teacher becoming the school disciplinarian or like the dean of culture, right? I've seen people who look like me dismiss that as anecdotal and, oh, that was your experience. And that's not true. Like, that's -- it's found in research, right? Like, toxic White dominant culture plays out in our head prep programs, and it plays out in our schools. And it plays out in nefarious ways at times and in subtle ways at time. And when, you know, wonderful -- we want all teachers, White teachers, Black teachers, and every -- all teachers to build positive cultures in the classroom that center on the whole child. And to say that, oh, but because we have students of color, it's just the teacher of color's job to make sure that happens. No. It's everyone's job. It's everyone's job, right?

And so culture issues do push teachers out, teachers of color out of the classroom.

[Kirsten Miller]

Okay. So I'm going to jump in and ask some questions around support. So particularly in the conversation we've had around there's seems to be this expectation that there's unpaid labor from educators of color, right, you know, going back to what Janet and Representative Bacon have said and, Steve, what you've expanded on a bit from the research. So, Janet, I wonder if I could hear from you on what made you feel most supported as you were starting your career as a teacher.

[Janet Damon]

So in those days I will say, like, when I first started my first year, there were six or seven African-American women who worked in my building who provided me not just, you know, support like, oh, you know, do you need me to get your photocopies? No. They provided me with mentoring. You know, they were interested in the ups and downs of my life. They were so kind to me, so supportive. I think about some of the work from Dr. Michelle Foster, who did -- you know, she examined the experiences of Black teachers, and she did a qualitative kind of study and analysis about our stories. And one of the things she found is that, you know, having two or three other people, not just being a singleton, you know, that has stayed with me throughout my career. I have sought and thrived under the kind of leadership that also is able to retain other women of color, people of color. So, you know, I work in a building right now that has -- you know, it's almost like a quarter African-American educators -- I mean, we -- this is my first time working with an Iraqi, Iraqi American, you know, and having the perspective, you know, that she brings from her lived experience.

And, you know, and having, I think -- so what I look for is evidence-based even in how I select places that I work. What's the evidence that it's a place where I can thrive? And so I know that, if other people have been able to, you know, dig and make roots there, then I probably can also thrive in that environment as well. So support to me looks like community. We know that people of color, put a lot of emphasis on, you know, community, building, about being in relationship with their colleagues, feeling the sense of camaraderie with them. And so I don't know if I could have that experience if I were the only African-American educator in a building.

[Rep. Jennifer Bacon]

You know, I was certainly not in the classroom for as long as probably our colleagues here on the podcast. But the thing that made me want to go into a classroom before I even kind of understood what Janet was talking about, was going and being there for my community. And I find in the work that I've done around recruitment, you know, I -- one of the things that was really important to me in my job, probably the last actual job that I had was actually to diverse -- I'm sorry, to diversify our Teacher Corps where we were kind of like one of the least diverse in the country. And we had like one Black teacher out of 200 to about 45 to 50% educators of color. And what we found is not only what will bring people to the space, even in this day and age where teaching may not be a glorified profession, there's something to be said about our communities actually understanding what education means to our liberation, whether that is consciousness; whether that is, you know, the way that we can thrive and live in community. And it is enough of a draw.

And then the experience turns into we call it the tax. You know, I was the dean of culture, they're always sent to our classrooms, you know, and don't get me started on Spanish speaking teachers and all the free translating they're doing, you know. And then what turns into the barriers are, the support within-building. Like, one, do you have network who can empathize, which I think is just generally an anthropological concept. But the second becomes can we lead, right?

And so we're often also I think, in the -- in maybe the last era of public education, a lot has been said about educating kids of color and Black kids and all of those things. And our bodies are typically used in the tokenizing type of way as tokens, but we're not able to actually lead. Or once you're in a leadership position, you're combating dominant culture and also trying to bring yourself in lead. And so we've started to call that in my little circle like the glass wall. Like, it's not necessarily glass ceiling, like you can see where you need to go and you keep hitting it because we've been put in positions where we can't lead or that we are overtaxed, right, when it comes to our capacities.

And so when I think about that as compared to why people get into the profession in the first place, it is a particular type of devastation, when people kind of, you know, become aware of those barriers and when they leave the profession, you know, because it's not just I want to do something great. I want to do -- I wanted to do a “we show” moment here, not a me thing, you know. And to run into that hasn't helped with this profession in trying to get people into the classroom.

So it's not just people talking about the pay is low. It's talking about the experience. And, you know, it's one thing to try to convince kids to become a teacher while they're experiencing that job, you know. So however their experience is if they're going to want to become a teacher or not. But it's another to talk to generations of folks who've had a chance to talk to each other about what it means to be a teacher and then what it means to really set some things aside to want to stay in the profession. You know, and I think that is something that is part of this generations, issues and concern. For Janet and our parents, as brilliant as everyone was, my mom had PhDs who taught her because they couldn't get other jobs as African-Americans, but they were used to an interesting type of quality. Teachers lived on the same street as the doctor and the janitor. And so our dynamics have shifted as a matter of culture. And then the narrative of the experience is particularly now to some of the things that we're talking about.

So, to me, it's not just about policies for the sake of policy, it’s really understanding a modern conversation of what it means for this profession because it's more than just -- you know, bank tellers are awesome. I could have been one. But you have to make conscious decisions now to be an educator. And it definitely comes from, for most people I would say, anecdotally, or whatnot, but it definitely comes from within. And then if the space doesn't match, it has such a deeper impact, you know, when people leave.

[Kirsten Miller]

So, as we think about that, I wonder if you have any further thoughts or anyone on the call, if you have any further thoughts around where we start that work? It's such a huge task to start those conversations within, you know, teacher preparation programs, potentially, within schools, Representative Bacon at the policy level, you know, you're having, having those conversations. And this is a little bit of a wish list, I think, at this point. Like, where do we begin to try to make some more inroads in those issues that we've all discussed and raised today?

[Janet Damon]

I think honestly, you know, I think part of it is I think about this work and through an ecological model, right. Before I get ready to reap the harvest, I do not go to the land and expect the harvest to be waiting for me. I know that it's going to take time and cultivation for me to be able to -- to be able to prepare the soil, plant the seed, grow it, water it. And so, you know, looking at our current state, how are we preparing our schools to be warm, welcoming spaces for educators because right now, at any given moment, you know, I have taught high school for a while. And there are students I can identify for you at 12th grade, 11th grade, 10th grade who can say, these are people we can really bring in, you know, to our schools in two to three years, four years, right. So having a program when we think about teachers identifying students who really have the kind of heart, capacity, desire to maybe become an educator and then thinking about, you know, post-secondary, you know, that Representative Bacon spoke to is that, you know, career and technical. Why don't we have these pathways so that we can move some of these students right into positions?

I have students who speak Arabic. I have one student here who is from Rwanda who speaks four languages and who writes in Arabic, right. So, at the same time, we always are decrying, we don't have enough people who speak the languages of our students. We have students who speak the languages of the families, right? So how do we prepare these translation services? How do we prepare them to maybe be educators?

And then, in that time, thinking about how do we rethink some of the ways that we respond to educators who are crying out for help? So one of the first places that I think about decolonizing is human resources. There's -- when people reach out, you can either have an experience where you are heard and there is accountability levers that come into play. There are equity coaching maybe that might come into play for a school leader or a department director. There are people who can mediate the conversations. But, you know, when I've had folks who have told me I cried out and the response was, you shouldn't have said anything. Now you are in trouble because of the way that you used a phrase or now, you know, like the levers are really triggered to protect the kind of bias and harassment and so forth that people are facing. They're not necessarily geared to help.

So I think when you think about what teachers are experiencing, where's the equity accountability procedures built into that first level of our structure around protecting individuals and honoring their humanity and then identifying, do I have systemic complaints coming from this school, this system? Are they coming from the parents and families? Are they coming from the teachers? Are they also coming from the students. And doing some deep listening, right, because the restorative work that needs to be required to bring about this kind of healing is not one and done, I met with you two times. The day is over, you know. It actually would require some intentionality and the same way that, you know, ecologically, anything that we plant would require us to do the kind of diligence to come back and check on it, to make sure the systems for watering, growth, all of those things are happening. So I do think that identifying and recognizing that we value students who are already demonstrating the characteristics that would make them great teachers and incentivizing them to say we have opportunities within our schools that we can pay for paras, para support and that -- or pathways into fields in education and then, at the same time, thinking about what can we do to some of the real strongholds and real gatekeepers for these institutions. And I think that HR is a big one for most organizations.

[Rep. Jennifer Bacon]

I've been thinking about two things lately, especially because they are political. And so I'm a politician. I can probably be a little bit more political here, and everybody knows where I affiliate. So, you know, I will say this. The first thing that is so important about this and we've talked a little bit about it is that, if a college degree is required to become a teacher, we first need to get kids to and through college. And as much as we want to talk about, you know, how many people are in teacher prep programs, we need to pay attention to K-12 to be sure our graduation rates are great, right, that our kids of color are graduating at proportionally, if not disproportionately high rates, just so that they can enter that profession.

You know, we -- part of the reason we only saw 36 is because the data also commiserate -- you know, the data is also the same that, you know, African-Americans aren't going to college or completing college at the same rates as their White peers, right. And so we need to keep our eye on that ball and be sure that those conversations are connected. And, quite honestly, it comes up for any workforce. You know, workforce politically is a hot-button topic right now. But we haven't made connections, I think, particularly in talking about people of color in the workforce. Right now, it's very number and data-driven. So, for example, in Colorado, we did a whole workforce study. We know, you know, 60% of people are -- need to have a tier-one degree or credential, right, to make a living wage. And somehow I see us paying for people to go to electrician school and people -- and us paying for people to become -- work in construction and health, but we're not doing the same, interestingly, paying people to go to college or to get a credential or those who are para, right, to become teachers. And so it's interesting how workforce in and of itself has become political. And even within that conversation, political as for who?

And so, as a side note, the things that legislators of color -- and I can speak for my caucuses, right? Are keeping an eye on is we cannot recreate a system so now we're tracking kids of color, you know, to go into certain professions. We're talking to a lot of kids of color about becoming CNAs, which is perfectly wonderful, but we're not having the conversations about them becoming physicians. Right?

And so the last thing I would say on workforce, too, is that, if it is something that we need to care about as a matter of state and policy, to sustain our communities because people are earning, there are a lot of people wasting a lot of political capital on things that aren't important, right. And so the most part of politics is about, as much as I would love it to be that the 100 of us, as legislators are Rhodes Scholars and all have MPAs and MPPs and PhDs, we are still just people. And you've got to get people to care.

And the problem with racism, whether it's explicit or implicit, is that people are either not exposed or they don't care expressly or they live in a world of stereotype. And they are latching onto things that they find more important because they don't connect the outcomes. So, for example, I find it odd to be in states with governors and legislators who are talking about workforce, workforce, workforce and then simultaneously use most of their political capital to ban curriculum, right, because, for what it's worth, nobody else in the world kind of cares about that right now. Everyone has kind of caught up to where the US is on manufacturing, on education, on sending kids to college. And we're using a lot of capital on talking about the quote, unquote upsides of slavery and then simultaneously saying and realizing we're not graduating kids, whatever degree or credential, to get them into workforce. And the question is, why is one more of a priority than the other? And what does that mean by way of political identity? You know what I mean?

And so all this goes to say is, for those of us who know that these things are important, we cannot necessarily just rest on our laurels and think it's going to happen. We have to be as active and engaged and talking about why these issues manifest in ways that deeply impact our communities and what our responsibility is to help build healthy communities, you know, and, like, bring that back full circle. So that matters what we're teaching kids of color.

I am very blessed -- I had two Black teachers, one my kindergarten and my senior year, you know, and my parents were the in-between. But not having those and then them helping me build my ties to connect to community and wanting to be of service to community and sitting at dinner tables with parents who had to sit in the back of a bus, you know, some of these things we have not been able to talk about as of late because other people want to be more grandiose in their noise. But we have not put our narratives back on the table to say these are actual community drivers, you know.

And so I think this topic is certainly about the policy tools and the levers, you know, if we are building system to these outcomes. And it should actually look like that. We should actually measure if we are recruiting and retaining people. But we also need to do our work to help people understand how important public education is, and educators are, to the fabric of our communities. And if we have five minutes, let's put our time into that, you know. And so I want everybody who can, like, understand what happens in capitol buildings and maybe the school board buildings. We need to be reminded of that these are the ways we hope you show up, right?

There are certain people who are definitely organized around being opposition. But in regards to the things we love, we also need people to show up and remind the legislators of that. We need people to say it matters if there's a teacher of color in this room. We need people to say spending three months on this curriculum, when nobody is prepared for workforce is not what we need our leaders to be doing, to just burst the bubble a little bit. So I hope maybe some of you might write your legislators after to just talk about how important these things actually are to our community.

[Kirsten Miller]

Thank you so much, Representative Bacon, and Janet for a wonderful conversation and Steve for your insight. I want to just open it up as we near the end of our time together here for any final thoughts from any of our guests.

[Steven Malick]

You know, obviously, we need to look back to be able to look forward and recognize that the systems, the policies and procedures that are in place are not there by accident. Someone made a decision at some point to build things out the way that they are, and someone is making a decision or someones are making a decision to uphold those systems. And so, you know, it is important that we deeply scrutinize because some of our institutions are built when we had an agrarian society, right. Like, central district offices only exist because we passed, you know, federal legislation and we needed an entity that would put money from the feds in the school's hands, right? So that's why kind of district central offices exist, right?

And, you know, White teachers can be effective, great teachers. But it means that they have to do their role and unpacking their own biases, recognizing the role in which racism is a systemic issue, and advocating that both within education systems and outside the education systems to dismantle those racist systems because, if your students of color are getting degrees because the system is fundamentally inequitable, you're not going to get teachers of color, right? That's what Representative Bacon said. You know, I just have to thank Representative Bacon and Janet. It's been really wonderful to meet you both and learn from you today.

[Janet Damon]

Likewise. I think this has been a really rich conversation. And thank you so much for moderating this for us. And I just -- I actually -- I have such great hope. And I -- you know, I tell my students, some of the -- what I think surprises me sometimes is how much our students see this overwhelming challenges that we've put forth on every media platform of how everything is really very terrible. And so some of the things I have to talk to them about is, like, we are the engines for change and hope, and so we cannot lose hope on any of these fronts.

And we have this beautiful Generation Alpha that's coming up behind us, the largest global generation in history. And they are open-minded. They are -- and so I tell my students who, you know, are our high school now, I said, you have to pay the way. You have to -- this struggle is not going to be completed in, you know, by one generation, by one group, one identity. It's going to take all of us in the relay race together. Each of us carries the baton for the length and the space that we are assigned to it. And then we pass that baton. We cheer on the next generation. We continue to stay engaged.

So my thing is, my last thought is, be hopeful and be a part of the good work and the good trouble and the good change. And the reward is that you at night are at peace with yourself that you've done all that you can do, and you move things for each generation to take its next leg of the journey and as leaders and as the workers of it.

[Kirsten Miller]

I think that is a wonderful stopping point for us today. So, again, thank you so much, Janet, Representative Bacon, and Steve, for being on this podcast with us today.

[Rick Stoddard]

Thanks again to our guests, Colorado State Representative Jennifer Bacon, Janet Damon, and Steve Malick.

And thank you for listening to another episode of On the Evidence, the Mathematica podcast. If you liked this episode, please consider subscribing to catch future episodes. We’re on YouTube, Apple podcasts, Spotify, and other podcasting platforms. You can also learn more about the show by visiting our website at mathematica.org/ontheevidence.

Show notes

Watch a webinar from REL Central at Mathematica on research and promising practices to support a diverse teacher workforce.