Recruiting and retaining workers has been a longstanding challenge for the child care and early education (CCEE) industry. Despite expectations to provide high-quality care and early education to young children, CCEE workers often experience low wages, poor benefits, low job status, and emotional, physical, and economic stress. It is no surprise, then, that annual turnover rates are as high as 25 to 30 percent—more than double that of K-12 teachers.

These systemic issues have been exacerbated by the COVID pandemic. Despite patchwork levels of federal, state, and local pandemic relief, many providers have experienced temporary or permanent closures due to demand shortages and increased costs associated with health and safety regulations. Exhaustion and burnout, low wages, and lack of benefits also drive teacher turnover and resignations. According to recent estimates, more than one in every three CCEE workers are now considering leaving their program, a figure that is even higher among racial and ethnic minorities and workers with less experience.

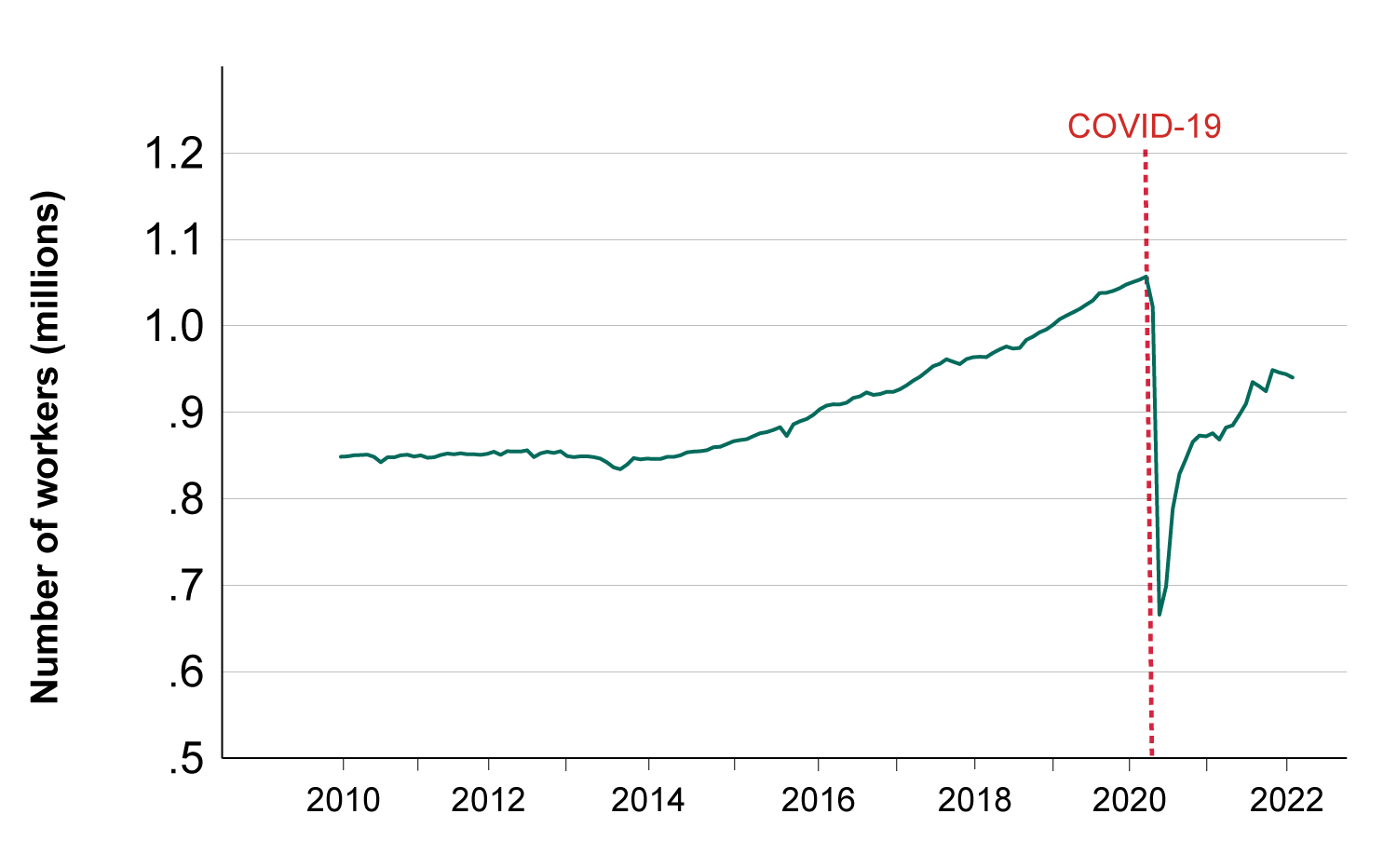

The number of CCEE workers in the U.S. plummeted in 2020 and has yet to return to pre-pandemic levels.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Current Employment Statistics.” Series Code: CES6562440001. Available at https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer/view/timeseries/CES6562440001.

Given the negative implications of inconsistent CCEE supply for young children, working families, and providers themselves, it is troubling that the number of workers has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels. However, our analysis of multiple data sources suggests additional cause for concern—that we are undercounting the CCEE workforce and may be particularly likely to omit home-based or unlisted providers who are especially prevalent in communities of color and areas of concentrated poverty, and who may face the highest rates of attrition.

Current methods of counting the national CCEE workforce

Precise monthly estimates of the actual number of CCEE workers come from the Department of Labor’s Current Employment Statistics (CES) survey conducted by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The CES captures highly reliable month-to-month employment trends across the economy and within specific sectors. CES is considered an establishment survey because it only includes the most formal business establishments. In the CCEE sector, this means that the CES data are most likely to capture workers in center-based settings, such as Head Start programs, state pre-kindergarten programs, or other community center-based settings. This also means that the CES might miss home-based providers, particularly when they are paid for their services but do not appear on federal, state, or local provider rosters.

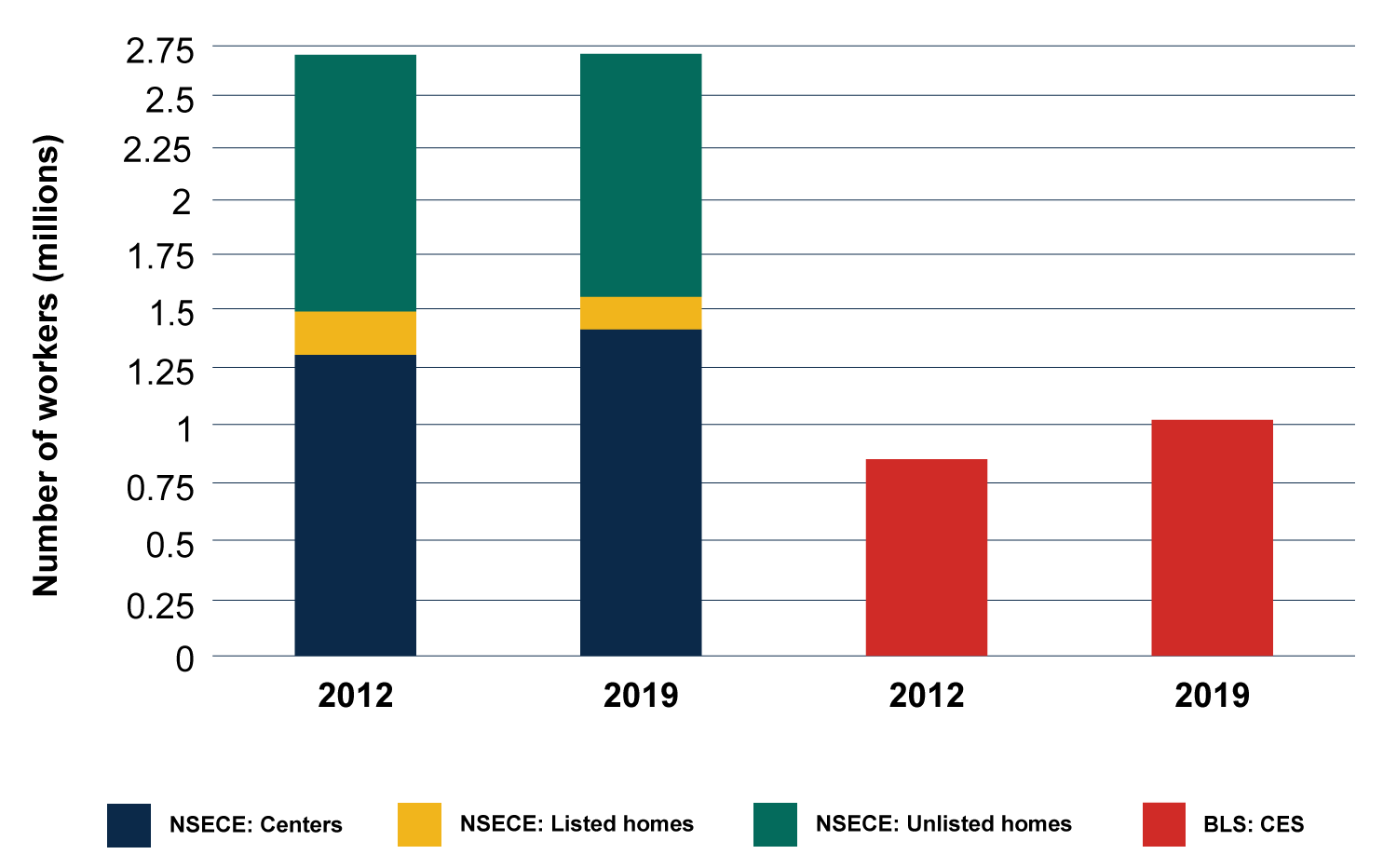

There are far more CCEE workers than the roughly 1 million that show up in CES survey data.

Source: Author’s calculation using the 2012 and 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) Home-Based Provider and Center-Based Provider public use data files and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics’ “Current Employment Statistics,” Series Code: CES6562440001.

The CES data number the CCEE workforce at about 1 million workers at the start of 2020. However, according to recently released data from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), a cross-sectional survey of the CCEE workforce conducted in 2012 and 2019, in 2019, about 1.4 million staff worked with children ages 0-5 in center-based settings alone, while an additional 140,000 providers worked in listed home-based settings, and about 1 million providers worked in unlisted home-based settings. These data further suggest that the number of home-based providers decreased between 2012 and 2019 (between 5 and 25 percent), while the number of center-based staff increased (8 percent). The CES documents a much larger 20 percent increase in the number of CCEE workers between 2012 and 2019.

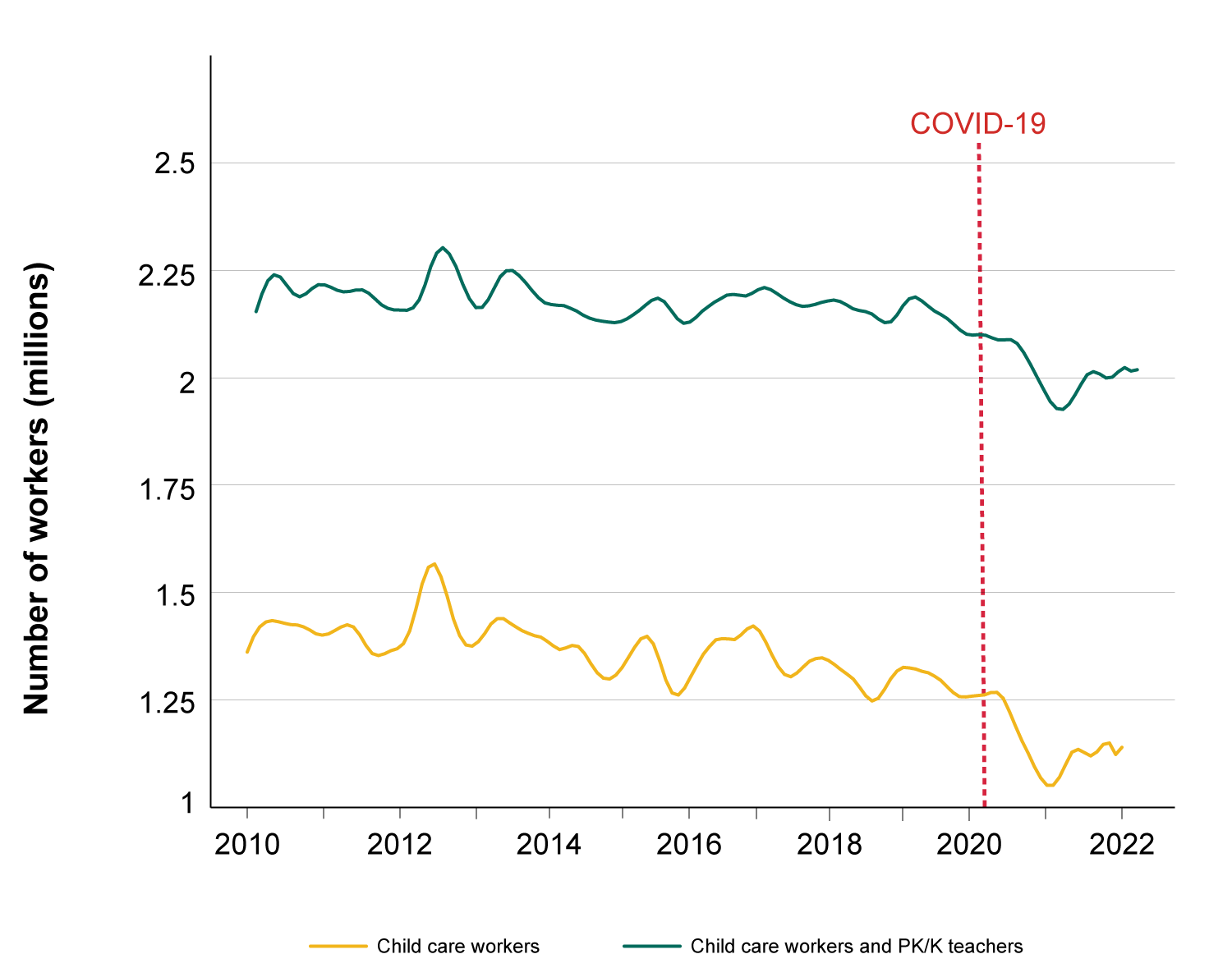

Data from the CPS provide an alternative, robust look at CCEE workforce trends.

Source: Author’s calculation using the Current Population Survey, available at https://cps.ipums.org/cps/.

Yet another data source, the Current Population Survey (CPS; also collected by the BLS), ties occupation to individual demographics over time. Unlike the CES, which samples establishments or businesses, the CPS samples households and surveys household members. This strategy is more likely to provide additional information about listed and unlisted CCEE workers who live in those households. Although less precise than the CES, moving averages in the CPS also show a dramatic reduction—by one-third or more—in the CCEE workforce immediately following the onset of the COVID pandemic, followed by a partial recovery. The number of CCEE workers is more in line with NSECE estimates, however, as are estimates of change over time.

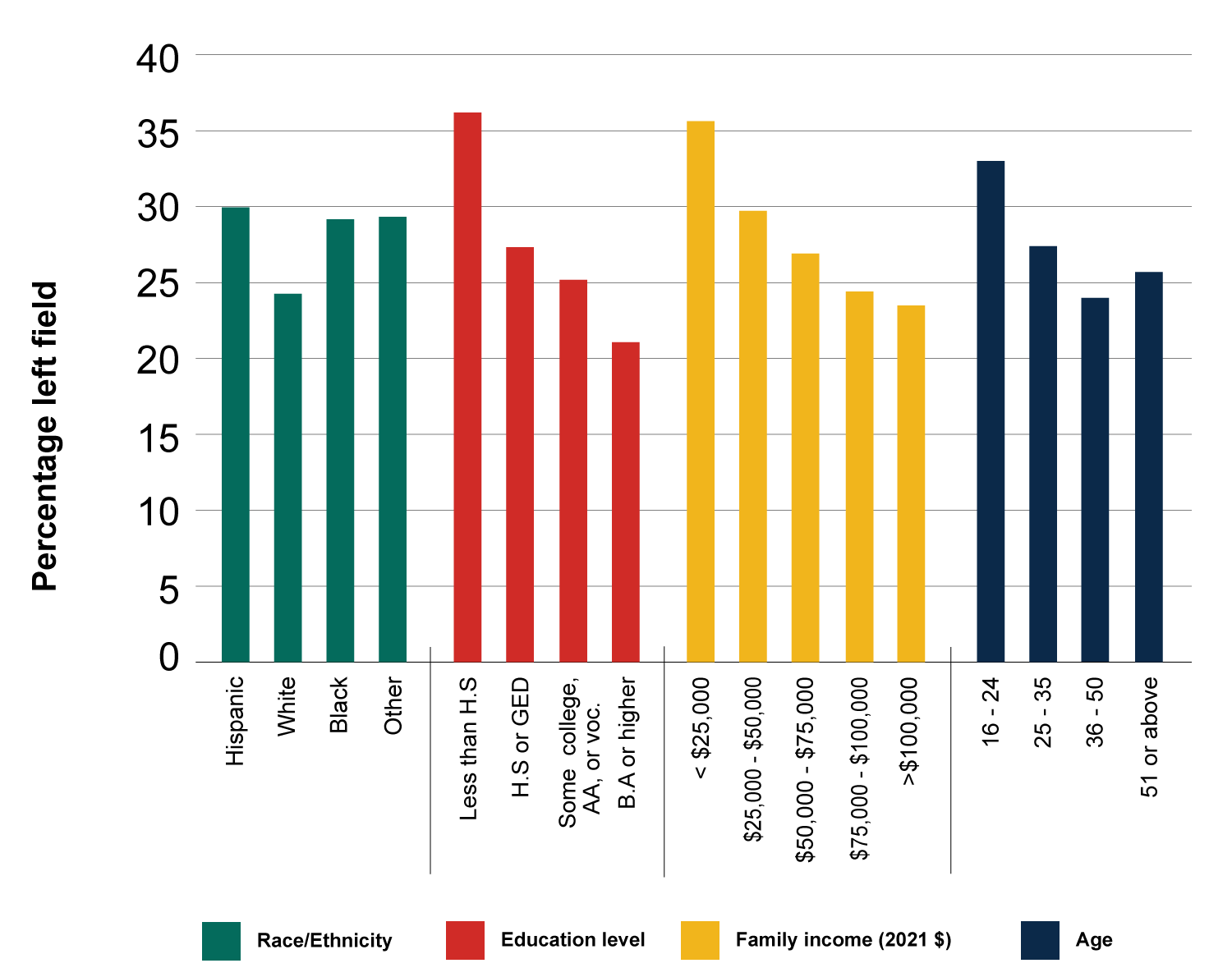

Because the CPS surveys individuals within households over as many as eight different months, the data also enable us to better understand which CCEE workers are leaving. In the upper range of prior estimates, approximately 28 percent of CCEE workers had left the profession since the last time they were observed in the data. We also examine the characteristics of the CCEE workers who are the hardest to retain.

Racial and ethnic minorities, workers with lower levels of education and the lowest household incomes, and the youngest workers with the least experience are most likely to leave the CCEE workforce.

Source: Author’s calculation using the Current Population Survey, available at https://cps.ipums.org/cps/.

Better data is necessary to address CCEE workforce challenges and support provider well-being.

The COVID pandemic has crystalized what we already knew to be true: CCEE workers fill a critical need for families with young children, particularly those with caregivers in the labor force. It has also strained an already-fragile market that struggles to retain existing workers and hire replacements when they leave. Addressing these challenges will require accurately documenting and describing the scope of the problem.

Although we lack a unified national CCEE data system, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners can each play a role in charting a course forward. Researchers can begin by coordinating best practices from federally funded data collection efforts. For instance, because the NSECE was developed to provide an extremely detailed picture of the CCEE workforce, it may be too costly to conduct frequently. Yet, best practices from the NSECE could be shared to improve the sampling and weighting of providers in the CES. The CES and CPS could also expand their occupation codes to better distinguish CCEE provider types using NSECE job definitions.

A more ambitious goal is a coordinated national workforce data system in line with what exists in K-12 education. Such a system requires encouragement and assistance from federal policymakers and implementation by states and local practitioners. Most states already have workforce registries, but participation is often voluntary or required only of providers that receive public funds. Some states also conduct workforce surveys, but these are not designed consistently and are often poorly funded. However, the federal government has recognized the need for an integrated CCEE workforce data system and has taken some early steps to address it. For example, the American Rescue Plan and other federal pandemic relief proposals explored mechanisms for data collection from state lead agencies to understand key characteristics of subgrantees. As part of the Biden administration’s ambitious Build Back Better framework, federal policymakers have advised states to collect data on CCEE initiatives and to build supporting data systems. These are important first steps toward addressing shortcomings in national data that underpin data-driven policy solutions to existing challenges in our nation’s supply of CCEE.