The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated pre-existing inequities that changed how individuals engage with pre-K programs, schools, colleges, employers, and the world at large. Early evidence suggests the pandemic took a toll on student learning, educational attainment, employment, and physical and mental well-being, especially in communities of color and communities experiencing poverty. In recognition of the fact that better data infrastructure will be needed to shift the systems that currently produce inequitable outcomes, a growing number of states are working to modernize statewide longitudinal data systems to understand the experiences and outcomes of individuals seamlessly across pre-K, K–12, postsecondary, and workforce systems.

This episode of On the Evidence focuses on efforts to advance equitable outcomes from cradle to career by making data more available and useful to state decision makers. The guests for this episode are Keith White of the Public Education Foundation Chattanooga, Naihobe Gonzalez of Mathematica, Sara Kerr of Results for America, and Ross Tilchin of Results for America.

White is the director of research and effectiveness at the PEF Chattanooga, a non-profit that provides training, research, and resources to teachers, principals, and schools in Hamilton County, Tennessee.

Gonzalez, a senior researcher at Mathematica, co-authored a recent report funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation on the Education-to-Workforce Indicator Framework, which establishes a common set of metrics and data equity principles for assessing and addressing disparities along the pre-K-to-workforce continuum.

Kerr is the vice president of education policy implementation for Results for America, where she leads EdResearch for Action, an initiative that fosters a more nuanced and effective application of evidence-based strategies by improving the quality, availability, and use of evidence in education.

Tilchin is on the solutions team at Results for America, where he directs the Economic Mobility Catalog, an online resource that helps local government leaders identify and implement evidence-based strategies, from early childhood education to workforce development, that can advance economic mobility in their communities.

Watch the episode below or listen to the episode on SoundCloud.

View transcript

[SARA KERR]

I'm excited the field is, I think, evolving in that direction of recognizing that evidence transcends, you know -- you know, rigorous randomized, controlled trials. There are other ways of knowing things. We are always going to be more likely to see better results if we are grounding ourselves in issues that our communities are excited and empowered to solve themselves and that they are going to put their support behind. And that's a really important form of evidence in and of itself are those lived experiences that folks on the ground are having.

[J.B. WOGAN]

I'm J.B. Wogan from Mathematica, and welcome back to On the Evidence. On this episode, we're going to talk about the investments we make in human capital and how we can do a better job of evaluating whether those investments are having the impact we want. An important piece of context for this episode is the COVID-19 pandemic. Early evidence suggests the pandemic took a toll on student learning, employment, physical and mental well-being; and the impacts were worse for communities of color and communities experiencing poverty. Not surprisingly, foundations, public agencies, and nonprofits around the country have sprung into action to mitigate those impacts. But how will we know if current efforts are working? We will need data, and we'll need those data to paint a holistic picture in a way they typically don't today. But our guests for this episode are working on ways to make the data more useful for gauging which policies, programs, and practices are moving the needle in advancing equity from cradle to career.

Our guests for this episode are Keith White, Naihobe Gonzalez, Sara Kerr, and Ross Tilchin. Keith is the Director of Research and Effectiveness at the Public Education Foundation Chattanooga, a nonprofit that provides training, research, and resources to teachers, principals, and schools in Hamilton County, Tennessee. Naihobe is a senior researcher at Mathematica. And she coauthored a recent report for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation on the Education to Workforce Indicator Framework, which establishes a common set of metrics and data equity principles for assessing and addressing disparities along the pre-K to workforce continuum. Sara is the Vice President of Education Policy Implementation for Results For America where she leads EdResearch For Action, an initiative that fosters a more nuanced and effective application of evidence-based strategies by improving the quality, availability, and use of evidence in education. Ross is on the Solutions team at Results For America, where he directs the Economic Mobility Catalog, an online resource that helps local government leaders identify and implement evidence-based strategies from early childhood education to workforce development that can advance economic mobility in their communities. I hope you find this episode useful.

Naihobe, we'll be talking about how state and local governments across the country can advance equity for their residents from their earliest years in preschool all the way to their time as adults in the workforce. But Before we dive into solutions, let's define a couple of related problems. So, first, why in 2023 are we especially concerned about inequities in education and the labor market? And, second, why is data so important for diagnosing and treating the problem?

[NAIHOBE GONZALEZ]

Thanks, J.B. Well, I think as you mentioned in your intro, we really have come to a head when it comes to a set of disparities and inequities that were really already persistent but, you know, have worsened as a result of the pandemic. We know because of the data that are available, for example, that there are persistent learning losses. Even a couple of years out from the pandemic, we still know that students haven't fully recovered. But we only know that for students who are in tested grades, for example. We don't know actually the extent of the problem for students in early grades or later grades in which, you know, testing is not part of accountability systems.

And we know less, too, about students who -- whose data maybe aren't disaggregated, such as students who our English learners or students with disabilities. And so just that one example sort of really shows us how important it is to have data to diagnose a problem and instances in which we don't have data to fully diagnose it. And it's hard to know, you know, how to act and where to make the biggest difference if we can't really, you know, quantify the extent of the problem. I mentioned only learning loss, but we also know both from data and anecdotally that, you know, people have been affected in myriad other ways, from social-emotional learning, mental and physical well-being, you know, all the way into obviously, like, career and employment. And so I think, now more than ever, we really do need holistic data to let us know how people are doing from cradle to career in order to then act and take action.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Sara, I want to turn to you now. When you're working with local education leaders through the EdResearch for Action Initiative, what data issues do you encounter that prevent state and local education agencies from understanding, number one, the disparities that exist; and, number two, which programs are most effective for addressing them?

[SARA KERR]

Sure. Great question. And thanks so much for having me here. I'm really excited to be part of this conversation. You know, interestingly, I'm not -- I'm not sure it's entirely or necessarily that education leaders have trouble understanding the existence of disparities. I think, in many ways, it's, you know, the pretty robust data collection efforts that have taken place at the state level and at the local level in school districts and in schools themselves that are really shedding light on those disparities. Naihobe just mentioned a few good examples. I think many of us have probably heard the expression, information rich, insight poor. I think that has rung -- you know, rung true, certainly in my career as an educator first and now as a policy person. This isn't to say, you know, that we can't improve our data collection efforts and disaggregation.

Naihobe, you just mentioned a few really good examples of where we could improve. But I do think that sort of collection and disaggregation of data has really come a long way. I also think it's really hard for all of us to do the arguably heavier lifting of making sense of the disaggregated data that we're collecting and really triangulating those data with other valuable data points, including the lived experiences of different individuals that we're, you know, intending to serve: kids, families, educators, etc., you know, the folks who are represented in those datasets. And it's sort of in that sense making a triangulation where, you know, I think the super important work of determining which programs and strategies are most effective for which students and under what conditions are happening.

And so, you know, I think we've spent a lot of time over the last three-plus years during the course of this pandemic really helping school districts and state agencies do just that, you know, bringing the existing data to the table alongside with the, you know, existing programs and investments and really trying to make sense of the data in the context of the work that's happening and the investments that have been made and working with leaders to, you know, strengthen the programs that are already in place and consider, based on those disaggregated data, you know, which students are being served well and which students are being, you know, served less well and how can we consider, you know, the data and the evidence together to determine new approaches that have both short- and long-term track record of effectiveness for the students they're focused on.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Keith, let’s turn to you now. Your professional bio says that your passion is, quote, turning data into information. When it comes to the kinds of education data you deal with in Chattanooga, Tennessee, what's the difference between data and information? And if you don’t mind, give us an example.

[KEITH WHITE]

Sure. And, also, thanks for having me. This is a great chance to chat with colleagues and really appreciate that I get to be a part. So when I talk about data, I'm talking about raw numbers. And I often have to admit that I am an educational psychologist. So I deal with data, do a lot of research, but I really come at it from a -- an individual point of view. So when I talk about information, I'm talking about data with a back story. And an example locally would be from -- in 2015, there was a certain way that the state derived economic disadvantage. And it put us, our district around 61% on that metric, which is a used metric in our field, obviously, the proxy for affluence or poverty. The very next year, that measure, with no changes in the population or influxes of economic juice, that measure was 36%. Right. So the data told me that that –

[J.B. WOGAN]

Yeah. That's a big shift.

[KEITH WHITE]

-- almost cut in half. Right. It was a huge shift.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Doing something right there.

[KEITH WHITE]

Well, the -- you know, the whole -- the whole issue with that change and how things are being measured. And I don't get into the why it was changed, the implications of it. It was never to make things more equitable in terms of resource allocation. But the data information distinction there was that the information that we were able to derive from that data was way more important, right, because we use economic disadvantage as an indicator for our -- how we target services, different awards, and this resource allocation in general. So instead of facing that local and dramatic impact, we got to be leaders in -- really, all we did was normalize the two datasets so people could see -- practitioners could see that it wasn't that we had half as many students who are facing issues related to poverty; it was the metric had changed fundamentally. And so the issues were still there, and we were able to kind of create a tool that helped them to see where students were in terms of that metric or where schools were. And that's -- that, I think, is the best example of turning data into information, right. It digs a little deeper than just taking this, oh, it cut in half, awesome, which isn't -- isn't an accurate response to that change.

[J.B. WOGAN]

That would also -- it would inform sort of the level of resources that policymakers think is required to address the problem if they thought that the problem had been cut in half versus having a more clear-eyed assessment that, no; it's just the metric had changed. Naihobe, I want to turn back to you. As I mentioned in my intro, you're a coauthor of a recent publication that lays out a framework for using data to promote equity and economic security for all. And this is a free and publicly available tool that people can use to understand current disparities and measure progress over time. So talk about why the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation commissioned the creation of this framework, who is meant -- who is meant to use it, and how they can use it.

[NAIHOBE GONZALEZ]

So I think, you know, collectively, we all believe in the power of data. But we also understand that existing data systems haven't always been designed with equity and action in mind. I mean, just historically, you know, a lot of the data that we collect was a response to accountability requirements, you know, hence why we have really good data on test scores and can say a lot about learning losses through test scores, you know, in the pandemic. So I think the framework was really born out of, I think, with a belief in the power of data and an acknowledgement that more can be done to really kind of unleash that true power of data in order to serve students. And so we worked with the staff in the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and Mirror Group, our data equity partner, along with leading experts from over 15 national and community organizations to develop what we truly do see as a framework for encouraging more equitable data use and, ultimately, ensuring that cradle-to-career data systems are set up to support students as they progress from early education through their career. And so, in terms of, you know, who can use the framework, you know, really, I think it's quite broad. I mean, the -- you know, it can be anybody who uses education-to-career data.

But we're really hoping that, in particular, it will inform longitudinal data systems because one of the goals that we have with the framework is to ensure that data systems are aligned from pre-K all the way into workforce so that data can tell the full story of that journey from cradle to career. And so I'll mention a little bit about how it can be used. The framework is comprised of a couple of different components. The first component is a set of essential questions which we have sort of identified along with, you know, input from a number of stakeholders in the fields as key questions that every longitudinal data system should be able to answer about students and their experiences. And so there are questions there related to students' experiences throughout pre-K through their career but also about how the systems themselves are serving them and what the system conditions are. Then we have a component that we call the indicators.

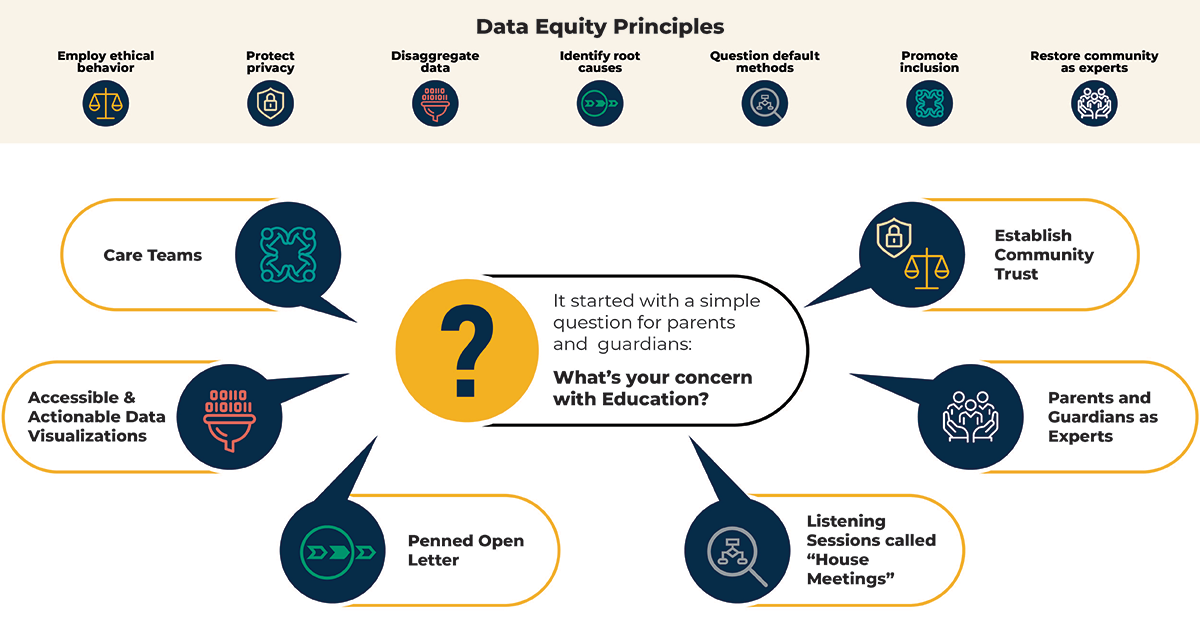

There are 99 indicators that we recommend to be collected again to span the full pre-K to career continuum. And we have recommendations about how to measure them so that the data can be out high-quality and actionable and comparable. Then we have a component that will be referred to as the disaggregates, which are a set of characteristics that we think it's really important to also collect so that the data can be disaggregated. Then we have a component that we refer to as the evidence-based practices, which is really now about, you know, taking data and thinking about how to use that data to take action and choose a practice that, you know, has a strong evidence-base and can address disparities. And then, last but not least, the framework includes a set of data equity principles that we really hope will guide data use through all of those steps that I just outlined. We acknowledge that, you know, data by itself, you know, can be neutral or even sometimes, you know, can be harmful if not used ethically and carefully.

And so we have put forth a set of data equity principles that we hope users will keep in mind when using data. It talks about things such as, for example, triangulating it with other data, which I think is a point Sara made but also involving community and restoring them as their -- as the data experts, since they're the ones who are often giving the data; and we're, you know, the ones interpreting it. So restoring them as data experts. So we really do see each of those components as being complementary. And we hope that, together, they can inform both the design of data systems as well as their use to make the data more actionable and equitable.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Ross and Sara, I’d like to turn to you now and talk a little bit about the work that you all are doing at Results for America. So you both spearhead initiatives that help local leaders identify evidence-based strategies that they can implement in their communities to increase residents access to opportunity. So could you talk a little bit about the intent behind the Economic Mobility Catalog and the EdResearch For Action Initiative and how people are currently using these resources.

[ROSS TILCHIN]

Absolutely, J.B., and thank you for having me. It's great to be here. So the intent behind the Economic Mobility Catalog is to help local leaders identify and implement evidence-based strategies to improve upward mobility for the residents. So this is a very wide-ranging resource that contains over 250 programs and strategies and quite a bit of overview, sort of brief style information on those. It also contains 50 case studies that tell the stories of how particular jurisdictions have been able to implement strategies that have good evidence and improve outcomes for their residents. So we want this basically to be a place where local leaders go where they can understand what the evidence says about a very wide range of strategies that have some bearing on upward economic mobility.

So whether that's education, it's health, housing, justice, and public safety, workforce development, you name it, if it has good evidence of impacting economic mobility in some way, we want it in the catalog. And then we want leaders to learn about the specifics of how they might actually implement those strategies. So what have experts said? What have practitioners said? What have the folks really doing the work in communities around the country learned as they've implemented these strategies? And then we want to distill those learnings in ways that feel actionable for users of the catalog so, if they do choose to pursue a particular strategy, they have a pretty clear roadmap of what it's going to take to implement that strategy well and get the results that they should be getting by implementing according to best practice.

So, in terms of how folks are using the resource, generally, they're coming to it with a particular issue area in mind. And they have very practical questions like, okay. Within my portfolio or within the policy area that I've been assigned, what are the strategies that have good evidence? What does the evidence actually say about what should happen if I implement this? What's the impact going to be if I implement this well? What's it going to cost? What are the essential components of implementation? So, essentially, the catalog seeks to anticipate those questions in advance, answer them as best we can, and then inform practice as leaders are deciding between a range of strategies and then moving forward towards implementation.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Okay, great. Can I ask one silly question? But just in case listeners aren't familiar with the phrase economic mobility or the term, do you have a layman's definition? How do you think about what economic mobility encompasses?

[ROSS TILCHIN]

Yeah. So, broadly speaking, we see economic mobility as the likelihood that a child born to a family with a low income is able to ascend the socioeconomic ladder over the course of their lifetime. Of course, there are other components of economic mobility or upward mobility, I should say, that aren't just captured by income, things like dignity, feelings of belonging, feelings of autonomy, being able to feel like you're in control of your own destiny. But the more strictly economic focused definition would be the chances of a child born to a low-income family rising up that socioeconomic ladder over the course of their lifetime.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Okay. And then the catalog is a place where people can find solutions within that area. Just very cool. It's a great website. Totally endorse people checking it out. Sara, what about the EdResearch For Action Initiative? Do you want to talk a little bit about what that is, what you do?

[SARA KERR]

Sure. I would love to. I think there's some good connective tissue between the work we're doing with Research For Action and the work that Ross and his team at RFA are doing with Economic Mobility Catalog and a few key differences, so happy to share a little bit more about it, including very briefly the origin story. At the outset, which of every Research For Action, which was in the earliest and darkest days of the pandemic when we were all spending way too much time in our basements and I think many of us trying to figure out how to be useful in an impossibly difficult moment, our big idea, and my co -- cofounder of that Research For Action and I's big idea was to broker trusted information about effective interventions and approaches between researchers and practitioners.

Both Nate, my cofounder and I, have had, you know, one foot in the sort of practice world and one foot in the research world almost our entire careers. And so we've been kind of playing in that liminal space quite a bit. And we felt like, at this moment, we recognize that education leaders, district leaders, in particular, were charged with practically overnight figuring out how to, quote, unquote do school in a dramatically different environment. And we knew that those leaders, you know, be making decisions, often, you know, super quickly, like I said, overnight having to figure out really difficult answers to tough questions. They were going to be making those decisions one way or another. And we thought, you know, our hope was that we could bring relevant evidence to bear on the questions that they had. And we believe that, if we could give them access to sort of easy to find, digest, and apply research, it would increase the chances that those decisions that they made about, you know, supports that they were putting into place, you know, for kids and educators, they'd be more likely to make a difference and positively impact the experiences kids were having at that point in time.

So that was kind of our big idea. And I think, in many ways, you know, three years later, that mission still holds true. You know, our briefs and other resources are really aimed at making, you know, often complex and conflicting, frankly, research more useful and, therefore, more likely to be used. You know, I think I'll mention one important way, I think, we've evolved over time over the course of these three years, which is, I think, hopefully reflective of the direction that education research in general is heading is that we now, I think, have a better understanding of where states and districts are and are able to meet them there. And by that I mean we have found that states and school districts aren't always looking to data and research to tell them what to do, especially right now. Three years into the pandemic, three years of federal relief dollars have flowed to districts. They've made a series of investments; and they're, you know, midstream or even quite a bit down the road of implementation. And what we've learned is that there are real opportunities for data and research to inform not just on the front end what should we do but how do we take ongoing data collection and research, take stock of what we're doing and really understand how we can strengthen the implementation efforts.

I think I heard, you know, all of -- all of the panelists or all of the podcast participants hit on the importance of implementation. And I think that has really been an important evolution of the research fraction initiative. And we're spending a lot more time focused on using data and evidence to better understand whether and to what extent the investments in evidence-based approaches are, in fact, making a difference and where they're not, using those same data and evidence to kind of drive either improvement of the initiatives or already investment -- invested in or, you know, new investments. We do this in a couple of ways, including through our Act on Evidence Toolkit, which I won't dive into the details of today but basically takes the underlying research that we all have access to that exists in our brief and kind of turns it on its side and gives leaders a set of look force to help, you know, understand the existing investments that they've already made and programs that are in place.

Just a few weeks ago, one of our close partners in a small district in Massachusetts, he's an assistant superintendent, was telling us about how he's using that Act on Evidence Toolkit as a summer planning tool with his principals. As they go into next year, they're taking stock of all of the work that they've been doing in the past couple of years and thinking about, you know, their existing student data paired with community input, paired with research evidence and using that as kind of a stocktaking tool as they think about the coming year and what they really need to do to be, you know, in this sort of final year of federal relief funding, in particular, what they need to do to make a difference for kids right now. And so that's a little bit of a flavor for what we've been doing. Much more on our website but so hopefully the highlights are always helpful.

[J.B. WOGAN]

That's really interesting. I was -- in preparation for this interview, I was looking through the website. I read one of the case studies by a school district in Rhode Island that was trying to adapt evidence on summer -- summer learning to the -- their resources to, you know, they couldn't necessarily do everything that the evidence suggested you have to do. And they also wanted to match kind of what were the local conditions and what the community wanted to do. I thought that was a really interesting case study in terms of exploring where the rubber meets the road. You know, being aware of what the evidence says is the ideal or best practice and then being able to implement something that is somewhat faithful to that but is also reflective of the real-world and the local conditions. Is there anything else you want to say? Am I capturing that correctly? I hope I'm not stealing your thunder for something you want to talk about later on in the show. Oh, okay.

[SARA KERR]

You actually sort of are, but I'm happy to speak to it now. No, I think it's a great point. And I think it's a really important point. And I imagine, you know, my fellow podcast panelists would agree that I think part of what we've learned and are hoping to, you know, kind of meet districts and states and schools where they are is that, you know, the evidence is super important. And the data is always super important.

But it's only part of the story when it comes time to -- for districts and schools to be making decisions. And so we're really trying to work with our partners to, first and foremost, ground whatever they're doing in their local context. And one of the needs of students goes back to this disaggregated data. What resources and capacity do you have? What support in your community exists for the kinds of things that you're trying to do? And then, you know, given that context, look to the evidence. And I think part of what we've tried to do with you were referencing, I think, the Woonsocket case study in Rhode Island. You know, they used one of our what we call our design principles briefs, which really takes a highly evidence-based strategy, in this case, summer learning programs and breaks it down into kind of the key characteristics of the program.

If you are someone trying to implement, these are kind of the 10 or so things that need to be true about your program based on the research evidence as you're thinking about design and implementation. We recognize that, given your context, you might not be able to, you know, do 100% of those ten things well, or it might not make sense for you to do it. And so we're trying to derive from the evidence where -- if this makes sense, where it's important to sort of hold tight and where you can let go a little bit and be looser in your design and align with the local context. And so it might come up later in the conversation. But I'm glad you picked up on that point. We had a lot of fun working with that district.

[J.B. WOGAN]

I did want to ask Sara and Ross about equity because it's so important to the work that Naihobe is leading with the framework. I was curious to what extent, when you're curating strategies, are you focusing on advancing equity? Is that -- is that a central part, or is that a consideration in the strategies that you're putting on -- that you're highlighting through either initiative?

[ROSS TILCHIN]

I'm happy to take this one first. And the short answer is yes. This is a really important part of the content that we're creating in the Economic Mobility Catalog. And I think that what Sara was just saying is a nice example of how we see sort of the broad approach of the Economic Mobility Catalog, and then we have a few areas where we focus on equity even more specifically. So, fundamentally, we think that every strategy in the catalog, when designed to meet local conditions, when put together in consultation with community adapted and all the ways that it should be adapted to meet a particular population can be a means of advancing equity. These are strategies that are proven to produce better outcomes that contribute to economic mobility. Greater economic mobility is creating a pathway towards equity. So these strategies, when they are designed correctly, can produce more equitable outcomes. More specifically, we have a range of strategies. They all sit within our outcome area. It's called racial equity in government that are a little bit more process-oriented that local leaders can look to as a way of changing the way that they do business, essentially, to produce more equitable outcomes.

So these are strategies like inclusive procurement. This was -- this is equitable employment practices when you're hiring for the public sector; equity focused budgeting practices when budget season rolls around, those sorts of things. So we have full briefs on all of those strategies as well. And then across all of our strategies, so there are 53 strategy briefs within the resource, all of those pages have an implementation best practices section. And many of those best practices have to do with implementing said strategy in a way that is equitable. I guess I should also say that we're excited to expand this content even more. So over the course of the next six months to a year or so we're going to be working with strategy specific experts to deepen that content even more in those implementation best practices, so this is even more at the forefront of the resource.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Okay. And, Sara, was there anything in terms of that you want to flag in terms of at Research for Action and the way that you all think about equity?

[SARA KERR]

Sure. And I'll be brief to, you know, share the air with other folks on this issue. I think Ross had a lot of points that are common in terms of the way we think about this on the research side of the house. You know, I think we often -- you know, we talk about how it's not just about, you know, average effects or outcomes overall but really, you know, supporting our partners to think about, you know, how the evidence, what about the evidence as it applies to specific groups of students and school personnel and specific needs. You know, many, many studies, far too many, I think, report on average effects versus effects on specific kinds of learners. And so we work with our research authors, you know, as we're producing briefs to, you know, try and, to the extent possible, identify relevant research for target populations and really work hard to isolate and report on subgroup impacts.

And we also try and hold ourselves accountable for not recommending strategies that haven't been widely tested and, therefore, you know, can be sort of safely considered as reliable and generalizable to entire populations. And so I'm like, veering on the edge of getting into really technical issues, which I don't think we want to necessarily do today. But it's really important to us in the context of the work we do with our research partners to help them understand that the folks in the field, school leaders, you know, district leaders, state leaders are really committed necessarily to equity. And that means being incredibly thoughtful about selecting approaches that are not -- that have been sort of studied and proven to be effective for the kinds of learners that they're prioritizing and trying to support.

So lots of technical pieces and components of that, but hopefully we're able to kind of tease that out in a way that feels simple and straightforward and accessible to leaders who are, I think, really trying to do the right thing and make sure that they're picking, you know, things to invest in that are going to make a difference for, you know, the students and families that are most important to serve and who have, I think, arguably over the last three years been most adversely impacted by the effects of school closures in the pandemic overall.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Keith, I want to turn to you. We've been talking about local partners, you're on the ground in Tennessee. And you've been involved -- so you've been involved specifically at the local level and working to link data systems across sectors so that people understand the current student experience from pre-K through the workforce and have the information they need to take action. If you don't mind, talk about what data you've linked together and why you've done that. And then I want to circle back to the next part, which is making that data useful.

[KEITH WHITE]

So we asked some school officials from local districts and focused a lot of our attention in that role on linking high school experience data, high school performance data with postsecondary data. We looked at the entire, you know, pre-college pathway, either really focus our attention on grades 9 through 12 and then into post-secondary so, you know, enrollment, persistence, completion. And that is important to us because that's -- first of all, it's not a part of the accountability model, so it doesn't always get a lot of attention. And so that's a driver for us. And we're a very equity focused organization. And, you know, we were -- we were seeing through lots of gaps after high school, right. So -- which obviously has workforce implications but, for our students, just quality of life implications. We take that information and share it with the district, share it with hiring partners. We have -- you know, we're in the healthcare agencies. We have a local public two-year and a local public four-year. Plus, we're right in the middle of the UT system. So most of our students stay in state in that -- in that -- in that space, one of those spaces. And we use the information internally as well for -- you know, we have a housing guidance programs, and we have student internship programs. And we have vision for local university. So we're able to really dive in and look at the student pathways and experiences.

[J.B. WOGAN]

And is there -- is there any -- can you think of any kind of illustrative example of how, once you've linked the data systems, how it's led to some kind of policy or programmatic change? Is there a success story you'd like to share?

[KEITH WHITE]

Sure. So I mentioned equity is a big deal. So we do lots of disaggregation. And, over the years, you know, we saw, as we worked on predictive models and early warning systems, we saw lots of students undermatching, which just means they were either not going to post-secondary after high school when they could have or they were entering a higher ed institution that was good, but they could have gone to a school where they had a better chance of success, which we measure by completion. So they would have graduated with a degree within six years. Because we saw undermatching, we not only looked at the data. I also talked to students about reasons for this. And even though it was a long process I won't get into, the bottom line was not all students were getting all the information.

Not all students were getting the information they needed to make great decisions or informed decisions about where to go to college or what to do after high school. So we took that knowledge and that information and used it to develop a post-secondary match that fit. We've got over 20 years of post-secondary pathway data and -- which is kind of a nightmare but also great because we're able to use that to build some predictive model that allows us to not have to dip into that data very, very often. So if a user or student gives us their information, we're able to help match them with a great school. So we look at an academic match and a personal fit and give them a list of schools at which they're going to have a greater chance of success. Obviously, that's -- comes with a lot of guidance, comes with a lot of support for -- we have embedded advisory system which comes into play as well.

So it's not like we just, you know, say there's your list. Enjoy. There's a lot of handholding and a lot of agency, as well, that we give the students. But I consider it a victory because it really did level the playing field in terms of who was getting what information, when they were getting it. And, you know, opened up -- opened up the entire menu of post-secondary options, whereas, you know, some of our students or most challenged schools were, you know, like, these work funnels, that that's what was happening. They were being either dismissed or just summarily sent to one or two locations without really much thought to fit, match, chance for success, anything like that, so -- and that was not okay with us. So that happened, something that we're really excited about. You know, the negative part about the opposite, we released it early in 2020. So we're still trying to collect good data on how effective it is and its usefulness in the field. So, as you can imagine, that wasn't a great time to release a college matching fit app.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Well, it still sounds like it's -- it has an obvious powerful potential. I think it'd be interesting to follow up and hear -- hear what data you collect about its effectiveness. I think one other question I had for you, Keith, was, if because this framework that I Naihobe mentioned earlier that Mathematica is working on with Mirror Group and for the Gates Foundation, you know, it is trying to gather data more equitably and also gather data on equity. What are the equity implications that come with changing the way we collect and use these data? Are there any -- any sort of general principles or examples you can think of in how you've dealt with this in Chattanooga?

[KEITH WHITE]

For us, it's really about what our job is doing good research. I'm not coming into the situation with bias or predetermined opinions, I guess. And the reason why I put it that way is that we were seeing with our students that they had been categorized in a way. So I might have a profile for them. You know, we have all this information, working with the district, working with higher ed institutions. And their profile looks amazing. It's exactly the same as someone who would go out, persist and succeed. And, for whatever reason, they would be put in the by a -- usually somewhere along the way, I'm going to indict -- don't want to indict any systems or people, but some grown up along the way and say, Well, you're not college material. You're just not a college kind of person. Or your brother wasn't a college person. You're not a college person. That's not for you. All -- you know, all the -- all the things we've all heard in the field, I'm sure.

So, because of that, and also the knowledge that, if you're from an affluent school in Chattanooga, you're three times more likely to graduate from college with a degree than if you're from an economically challenged school, which is huge, right? Like, that's -- that's amazing. Amazing difference, usually not in a good way. So leveling that playing field, making sure that no matter what school you go to, no matter what one specific person or group of people might say about your past or your future or your potential, arming students with information and the advocates that work with them with good information, that's how we get at equity. And, to do that, we have to really just not only use the information internally but also use it with the students, with their parents. It kind of circles back to the answer, my answer to the first question. It's all about the conversation.

So data can sit cold, that information is meant to be shared, talked about, used. And, for us, that is the greatest equity lever is you're able to show a student, you know, when they say, Oh, I'm just not college material, to show them that, well, actually, if you look at other kids from your school who have gone and succeeded, you are perfect for college material and, you know, just to see that switch flip and their eyes light up a little bit, or their parents kind of realize, Oh, really? And then you get to see them change, all right, could change paths completely as far as that's the -- that's the best kind of equity, right.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Yeah. That -- what a nice distillation of the power of data and the human impact there. Can see the -- can visualize that child's eyes lighting up -- lighting up. I want to wrap up by looking to the future, and I'll put this question to each of you. What do you consider the next frontier or phase in leveraging data to advance equity across this continuum from education through the workforce? What still needs to change? Or -- you could take this different ways. What still needs to change, or perhaps where do you see an emerging trend that gives you hope about using data to inform strategies on the ground? And, Naihobe, I'm hoping you can start us off here.

[NAIHOBE GONZALEZ]

Sure. Well, it's hard to believe but, currently, fewer than 20 states actually have longitudinal data systems that connect data from pre-K, K-12, post-secondary and workforce, which enables, you know, the kind of data use that we've been talking about. So there, you know, is still a long way to go. But, on the other hand, I think we are at a time of opportunity. There's several states, almost 30, that have proposed using federal funds from the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund to either link their data systems or make other improvements to their data systems. And so it does feel like, you know, now's the time when people are thinking about the power of data and trying to go beyond kind of what we've been doing, which, you know, again, you know, was sort of really focused on accountability for a long time and now trying to go beyond that. There are a couple of states that I think really serve as, you know, sort of promising case studies.

For example, both New Mexico and California have really been using an approach that is based on starting with the central questions, you know, working with stakeholders to identify what are the key questions that they want to be able to answer with their longitudinal data systems and then using that to inform their data modernization efforts. And so we hope that more and more states and communities will use that sort of approach, which we hope will help ensure that the data are more actionable because too often, you know, there's accountability and different rules. And that sort of guides what data gets collected. And then that in turn, guides what data gets used. But we hope that by starting with, you know, the questions that really need to get answered in order for people to take action, you know, that serves as a promising blueprint for making sure that data modernization efforts going forward, you know, are leading to data that are more actionable and can support more equitable data use.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Keith, what are you looking for? What do you think is next in I don't know if you want to call it the fight but in the -- in the push of the movement to advance equity and using data to advance equity across this continuum of education to the workforce?

[KEITH WHITE]

We're going to see not necessarily a shift but an addition of another set of ABCs. So, you know, we've -- I talked about earlier about attendance behavior. Course completion is very quantitative, relatively easy to measure things. I think that we're going to need to get much, much better at measuring agency, belonging, connection because, you know, we've had two decades now of collecting some pretty high-stakes information. And we've learned. So I think -- or hopefully we've learned or will learn that that did not give us all of the answers we need to have actionable equitable systems.

So it's good news. Naihobe, for all -- for all the states that don't have a system yet, they can just build those new ABCs into their new system. Or maybe to start with agency belonging and connection and see if they even need all the other -- the other metrics. That's -- that's where we're going. And, you know, in addition to, you know, fellow panelists who are already doing that kind of work and thinking that way, again, there's a lot of great work out here, University of Chicago as well. They've got a great framework for that. And I think that's going to be where we hopefully we'll be spending more time and attention.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Ross, I remember, actually, you were -- when you were defining economic mobility, you were talking a little bit about the -- sort of more broader -- the broader concept of mobility and what's not necessarily captured in economic mobility but in upward mobility. And it seems very consistent with some of the things that Keith is calling for being measured in the future. Anything else you would add in terms of the next phase, the next frontier? What -- what's -- what needs to happen in the future in terms of using data to advance equity?

[ROSS TILCHIN]

Yeah. I think it's going to be increasingly focused on implementation here. So, first of all, I think that the frontier is sort of changed with great resources like the one that Naihobe and her team have created that give leaders in government the ability to really assess the landscape of where they stand and then make much more informed decisions on where their investments should go. So, with the creation of this resource that we're talking about today, others like the Urban Institute's Mobility Metrics, these are really powerful tools that can enable government leaders to be making dramatically better decisions. So I think that the frontier has shifted recently with that. But, with the focus on implementation, I think that there -- we're going to see a greater emphasis on trying to distill down sort of what Sara and her team often do with EdResearch for Action. So what are those essential components of, let's say, an after school program or a summer learning program, social-emotional learning curriculum in schools? What are those seven, eight, nine things that, if you are making an investment in this strategy, you really need to have in place in order to get the intended effect?

And once we're able to see more information on those core components, you know, stretching beyond just the educational realm but into things like health or housing, workforce development -- development, you name it, that gives local government leaders a ton of leverage as they're making investments in these strategies where they can say to, you know, during a procurement process, during a budgetary discussion on how to allocate funds to a particular program, this is what we really need to have because this is what's going to generate results. So I'm really excited to see more work in that realm.

[J.B. WOGAN]

Sara, I want to give you the final word. And I know Ross has already -- he talked a little bit about implementation that connects back to some of the comments you were making earlier. But is there anything else that you want to speak to in terms of the next frontier, what to look for in the future, what needs to happen now and in the future for advancing equity through data?

[SARA KERR]

Always dangerous to give me the last word, but I'll see how I do. I mean, I just want to, like, you know, underscore, cosign 1,000% all of what everyone has already said. It's always lovely to be able to build on those ideas and walking away with new information. I love the new ABCs, Keith, so I'm -- I didn't -- I understand those concepts and 100% agree that that is part of the next frontier is really rethinking how we -- you know, what we're collecting and how we're using that information to understand the entire, you know, experience students are having and, you know, use it to support them and predict how likely they are to be successful along their trajectory.

So excited to walk away learning something from this, not just that but lots of things. I wanted to double down on the implementation piece because it's just been so clear over the course of my 20-year career that that is really, you know, where we need to be more focused. You know, I think that there is -- historically has been less time and energy going into implementation than I think is ideal and that I think is necessary, for all the reasons Ross and others have already said. You know, I think even the most highly -- I've seen it, right, myself. I've been behind implementation of, you know, even the most highly evidence-based, you know, solutions, and I've seen them fail because we didn't attend to the details of implementation.

You know, do we have the adequate resources, the human capital, the community support. I want to just like triple underscore that. I think we've really come to understand the importance of, you know, starting -- Naihobe, I think was saying this and others, like, start with the questions that communities are asking and the issues that they're seeing and experiencing and the problems that they want to solve. I think we are always going to be more likely to see better results if we are grounding ourselves in issues that our communities are excited and empowered to solve themselves and that they are going to put their support behind. And that's a really important form of evidence in and of itself are those lived experiences that folks on the ground are having. And I think I'm excited the field is, I think, evolving in that direction of recognizing that evidence transcends, you know -- you know, rigorous randomized, controlled trials. There are other ways of knowing things.

And I -- I think I'm excited for the resources that are being put out by folks here and others that are, I think, acknowledging that there are lots of different ways that we can come to know whether or not something is going to work for a certain population of folks, inclusive -- includes causal evidence that transcends that and excited to see that, you know, be more widely understood and embraced and couple that with, you know, sort of a relentless focus on implementation moving forward and building sort of those evidence building and continuous improvement muscles and then grounding them in, you know, the resources, the longitudinal data systems that states are investing money in moving forward.

[J.B. WOGAN]

I think that's a great note to end on. There's no danger at all giving you the last word, Sara. So Sara, Keith, Naihobe, and Ross, thank you so much for your time today. It's been a really great conversation.

And I will be sure to include various links to all the resources, the excellent resources so other people can learn more about the framework and the Economic Mobility Catalog and the Ed Research For Action Initiative and some of those case studies that we've talked about today. Thank you so much.

[outro music]

[J.B. WOGAN]

Thanks to our guests, Keith White, Naihobe Gonzalez, Sara Kerr, and Ross Tilchin. Any resources we discussed on this episode are available in the episode show notes. As always, thanks for listening to another episode of On the Evidence, the Mathematica podcast. This episode was produced by the inimitable Rick Stoddard. Subscribe for future episodes on YouTube, Apple podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you listen to podcasts. You can also learn more about the show by visiting us at mathematica.org/ontheevidence.

Show notes

Explore the Education-to-Workforce Indicator Framework.

Learn more about the Economic Mobility Catalog from Results for America.

Learn more about EdResearch for Action from Results for America and the Annenberg Institute at Brown University.

Watch a webinar with Mathematica, Mirror Group, and the Data Quality Campaign about increasing collaboration and alignment across local, state, and national data systems to help address disparities along the pre-K-to-workforce continuum.